Contrary to reports claiming Malaysia is 100 percent electrified, a significant portion of Orang Asli communities remain left behind and in the dark.

Some 142 Orang Asli villages - or 17 percent of the community - remain unelectrified, according to official data.

One of those villages is Kampung Sudak in Gerik, Perak.

It affects literacy rates of children growing up in the village, said village leader Deney Abain. This is on top of mobility issues which makes it hard for them to access the closest school.

Reaching the village

Getting to Kampung Sudak is a challenge in itself.

To get there from Pulau Banding jetty, one must travel roughly an hour on motorcycle or 4x4 vehicle, first through Rancangan Penempatan Semula (RPS) Banun, a resettlement village.

Part of Banun RPS is the Orang Asli village of Kampung Desa Damai.

The Jahai of Kampung Sudak, who are traditionally nomadic, link themselves to Kampung Desa Damai. This village has access to electricity.

A large number of Orang Asli villagers were resettled in Kampung Desa Damai but as families grew, some started moving out.

Some 70 villagers returned to their ancestral lands not far from the village about a decade ago. Some make up the villagers of Kampung Sudak.

But they often return to Kampung Desa Damai to charge their mobile phones, which they need to communicate with those outside the village.

Kampung Sudak villagers told Malaysiakini that the Orang Asli Development Department (Jakoa) does not recognise the village because the residents are supposed to be staying at Kampung Desa Damai. As such, Jakoa representatives don’t visit to audit the amenities.

When contacted, Jakoa said the Orang Asli cannot just settle wherever they please.

“Any establishment of a new settlement must be negotiated with the state government that has the power to deal with land matters, as stipulated in the Federal Constitution, before it is registered as an Orang Asli village.

“Jakoa is worried that the opening of new unregistered settlements will cause dropouts and fall behind in efforts for the government to provide development, infrastructure and assistance,” it added.

The department noted that nomadism is a way of life for a “small number” among the Orang Asli and that “the government respects this way of life”.

However, Jakoa said this lifestyle is “rarely practised” because various basic facilities and social amenities available in villages make life easier for the Orang Asli community, to a considerable extent.

Fearing wildlife conflict

As one travels further into the interior of Banun RPS, the route eventually breaks off into a smaller off-road path, accessible by motorcycles and 4x4 vehicles.

At this point, elephant footprints can sometimes be spotted, indicating that this forest reserve is the endangered species' habitat.

There are less than 1,100 elephants in the wild in Peninsular Malaysia. The local communities who fear their presence often refer to the animal as “orang besar”.

In the last few months, Orang Asli communities have felt the brunt of human-animal conflicts, losing their homes, crops and in several cases, lives.

Recently, an elephant trampled the village leader’s boat. Since then, it has been hard for Deney to travel in and out of the village.

“That’s why it is important to have light. Otherwise animals will come and disturb us. There are ‘orang besar’ (elephants) in the area around Maghrib (dusk) time,” he said.

In 2017, Pahang’s Wildlife and National Parks Department (Perhilitan) introduced solar-powered LED lights as a solution to prevent elephants from encroaching human settlements in Kuala Medang, Lipis.

According to state Perhilitan director Ahmad Azhar Mohammad, this brought down elephant encroachment into agricultural land or villages at night by 90 percent.

Solar doesn’t always work

Over the years, there have been various attempts to bring light to Orang Asli villagers using solar power.

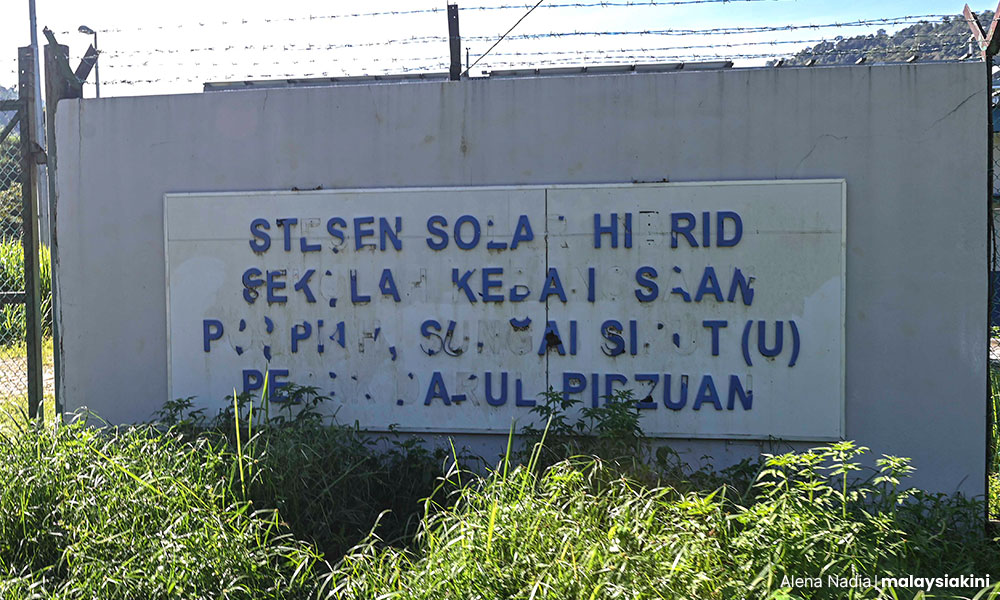

Pos Piah, within the Piah Forest Reserve in Sungai Siput, Perak, has enjoyed electricity supply since 2014.

With its paved roads and street lamps, Pos Piah appears in stark contrast with the more rustic Kampung Sudak.

Before it had electricity, Pos Piah flirted with solar energy systems.

But the system was not sustainable as locals were not trained to maintain the panels, a villager who wishes to be identified only as Arman told Malaysiakini.

The solar panels - located near a primary school - are said to have fallen into disuse since the village’s leap into electrification.

Even so, being on the grid doesn’t mean the lights are always on.

Sols Energy is a Kuala Lumpur solar energy company which worked on electrification projects for Orang Asli communities.

Its strategy director Hakim Albasrawy said even after they were hooked up to the grid, only villagers who can afford to pay the electricity bills would turn on their lights.

This means while households are out during the day earning a living, mornings and evenings at home are still often spent in darkness.

In Kampung Desa Damai, some households that could not afford to pay their electricity bills have gone back to living without power.

For example, he said, they cannot use electricity-powered machines on their farms to raise the value of produce grown, and they cannot keep harvested produce fresh.

It also impacts the types of food available for their own consumption, he added.

“Because refrigeration requires consistent energy access that directly impacts what kinds of food are viable in the village and the cost of access to these food,” he said.

Economic costs and political will

Hakim said besides the Orang Asli, many other communities in East Malaysia also face electrification issues.

This is mostly because many of the communities do not live close to the grid, and in some cases, the population is so small, it does not make economic sense to extend the grid, he added.

In some instances, the issue seems to be political will, like in the Perak Orang Asli village of Kampung Sungai Teras, which finally got electrified in August 2020, a week before the Slim by-election.

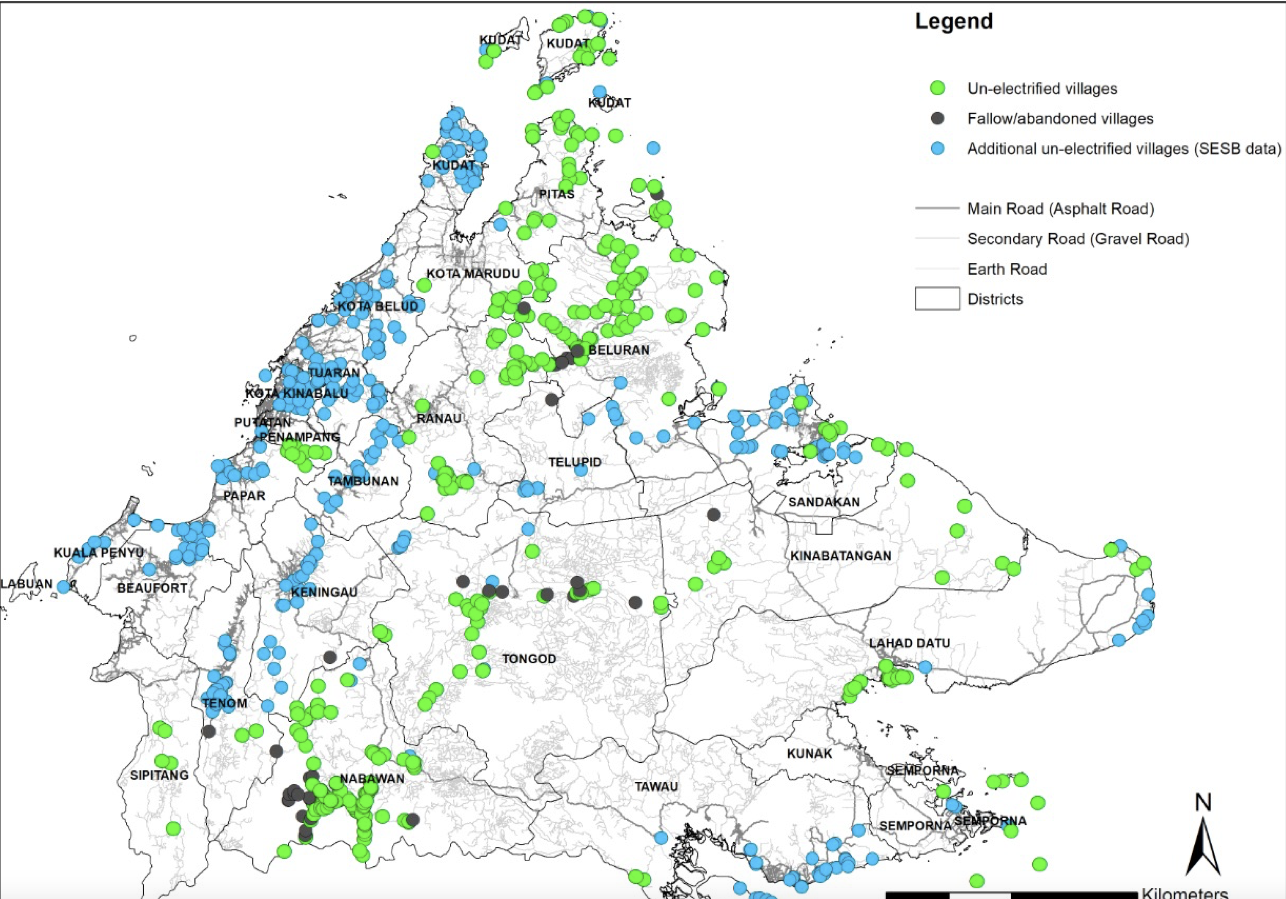

“In Sabah alone, the Sabah Renewable Energy Rural Electrification Roadmap (SabahRE2) consortium has mapped out 250-plus out of a known 400-plus villages that are off-grid,” Hakim said.

Unelectrified villages in Sabah

To view an interactive map showing the details and conditions of these locations, click here.

Many rural dwellers are without electricity, almost three decades since the Malaysian Electricity Supply Industries Trust Account (Mesita) was set up. Among others, Mesita funds rural electrification programmes.

Founded in 1997, every power generator is obliged to pay one percent of their electricity sale to the fund, but the government says hundreds of millions of ringgit are in arrears.

In 2020, then minister in charge of energy, Yeo Bee Yin, told Parliament that independent power producers (IPPs) owed RM197.9 million to Mesita for the period of 2008 to 2018, and a further RM50.7 million to Sabah Mesita for the same period.

It is unclear how much of the outstanding payment has been made since then.

However, more than RM800 million from Mesita has been spent on 180 programmes and projects since 1997.

They include grid connection projects from 1998 to 2014, the Malaysia Renewable Energy Roadmap, the National Energy Awards and development programmes on green technology in secondary schools, said the Natural Resources, Energy and Climate Change Ministry (NRECC).

Off-grid solutions

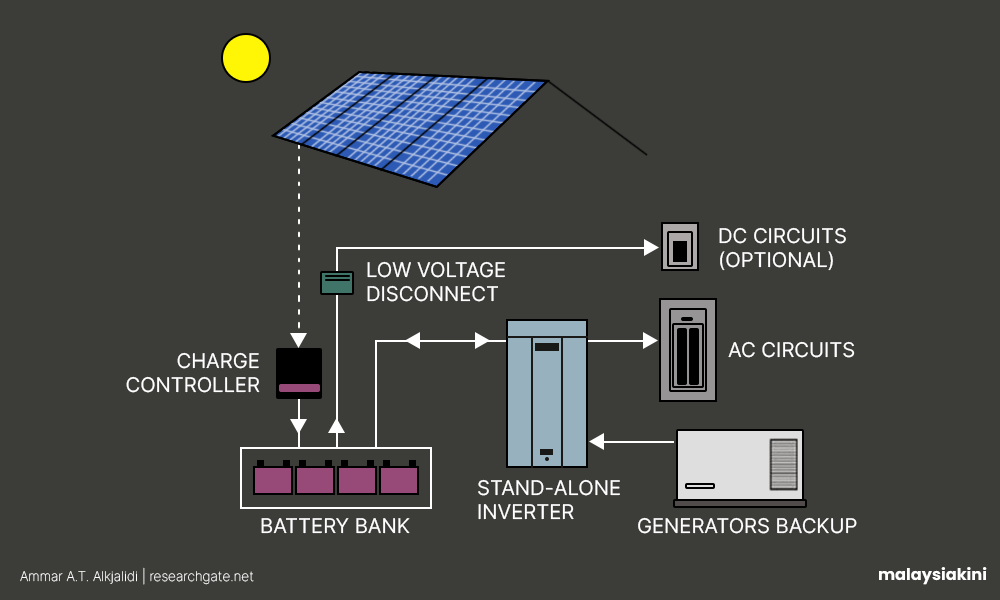

Part of the work Sols Energy has done involves community projects where off-grid communities such as various groups in the Orang Asli communities are supported with customisable off-grid projects.

The projects involve using a small 50W solar panel to power up lithium iron phosphate batteries that can last up to eight years. This is ideal to charge small devices and LED lights.

Hakim said this isn’t the end solution, but it gives communities access to electricity while waiting for permanent solutions. And without burning a hole in villagers’ pockets, like in the case of diesel generators.

Off-grid electrification projects for Orang Asli villages are also funded by the Rural and Regional Ministry, and implemented by TNB with cooperation from Jakoa and village chiefs.

“When the projects are completed, representatives of the community are trained as caretakers or operators to perform basic operation and troubleshooting procedures,” TNB said in a statement to Malaysiakini.

Besides TNB, Jakoa also works with other groups to provide amenities for Orang Asli communities.

This includes groups like Petronas, which assists in installation of solar panels, the Minerals and Geosciences Department which helps build tube wells for villages without access to piped water, and the Health Ministry’s unit which works to stop the spread of water-borne diseases through clean water supply systems.

Reaching renewable energy targets through rural electrification

Rural electrification should not just be seen as a charitable cause, said Energy Action Partners, a group working towards improving access to sustainable energy.

Instead, it should be part of the nation's renewable energy policy, which has largely been skewed towards urban centres, Energy Action Partners executive Ayu Abdullah said.

Malaysia has set a target of 31 percent total power generation installed capacity from renewables by 2025 and 40 percent by 2035.

NRECC Minister Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad believes Malaysia is on track to meet the target because installed capacity for renewables now stands at 25 percent.

But this doesn’t mean a quarter of Malaysia’s electricity is generated from renewables. In fact, the figure is much lower.

In 2018, the total production of energy supply (TPES) from renewables stood at about 7 percent, less than half of the 2040 target of 17 percent.

To meet the targets, the government is banking on large-scale solar plants, and large hydroelectric dams.

But Ayu believes rural electrification should play a more significant part in meeting these targets.

“(We should place) a greater priority on rural electrification in our energy policy, driven by understanding its importance and connections to other goals,” she said.

With rural electrification through renewable energy, Ayu pointed out communities not only have access to sustainable energy but also help them achieve better socio-economic development, engage in more enterprise and access better health, education, and information services.

This could reduce rural to urban migration and lighten the stress on big cities as well, she said.

In turn, the culture and heritage are preserved, and this is also a way to validate non-urban, alternate lifestyles, she added.

“It’s not just about urban lifestyles.”