Alex* was in an office meeting when he suddenly received a string of missed calls from his mother. When he called her back, she was panic-stricken.

She informed him that she had just paid an RM20,000 ransom to release him from police custody.

“The distress in my mother’s voice when I returned her call is something I still remember vividly,” Alex said.

Less than three hours before Alex spoke to his mother, she received a phone call from individuals who claimed to be police officers.

They informed her that Alex was detained for unlawful drug possession.

For him to be released without criminal charges and not be harmed while in custody, they solicited a bribe of RM50,000.

During the call, Alex’s mother was also taunted by the sound of someone in the caller’s room repeatedly pleading for help. The person’s distressed voice sounded like Alex’s.

Terrified for her son’s safety, she agreed to transfer whatever she had.

Alex’s mother dropped everything she was doing to go to her bank’s nearest branch and make the necessary transactions. She told the bank officer it was for house renovations. She withdrew RM20,000 – the entire content of her savings account.

When Alex finally returned her call, the relief his mother felt when she realised he was safe at work quickly turned to anguish. It was confirmation she had been scammed.

“When she called me, she already had an inkling that she had been scammed, because the ‘police officers’ who initially called her stopped responding immediately after she had transferred the money,” Alex said.

His mother, still scarred by the incident, declined to speak about it.

Billions lost in scams

In the same year that Alex’s mother lost her savings, more than 26,000 individuals in Malaysia suffered the same fate.

That year, RM700.2 million was lost to scams, including RM199.4 million in phone scams like the one endured by Alex’s mother. The trend is not abating.

In 2023 alone, at least RM1.3 billion was lost in about 30,000 cases of online fraud.

While enforcement, technology and security loopholes continue to favour scammers, part of the reason scams continue unabated is the perpetrators' ability to manipulate human nature, criminologist Akhbar Satar said.

“No one is immune to online and phone scams.”

Psychologists agree.

Take this example by US psychologists Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris, whose work involves studying human intuition and cognitive habits, and how these make humans vulnerable to deception.

“Impressive, right? Not if we tell you that we could not possibly remove the wrong card. We don’t really know what card you picked.

Left only with the evidence they (the audience) still have in mind, are virtually guaranteed not to think about the other cards,” the psychologists wrote in their book Nobody's Fool: Why We Get Taken In and What We Can Do About It.

Now consider this.

To function normally in life, we are wired to generally believe that everything is safe and true. Our default setting, Simons and Chabris wrote, is to believe.

“Thanks to our truth bias, we trust that what we are seeing is at least a close approximation of reality and that we’re not being deliberately misled.”

Ironically, when combined, selective attentiveness and truth bias can be used precisely to mislead.

They are among the arsenal of tricks employed by scammers to manipulate otherwise reasonable individuals to part with large sums of money.

Fight or flight

The most common tactic, said Kuala Lumpur-based psychologist Alvin Tan, is creating a situation of distress, to trigger a “fight or flight” response.

“(Under news reports of scam incidents), you can usually read comments of people asking why the victim didn’t do this or that. Because the solution to avoid the scam is quite obvious.

“But when we’re in a state of panic, shock or fear, we cannot make those decisions rationally,” Tan said.

Tan said this human tendency is so normal that it is primarily what many psychologists work on with their clients in therapy.

“The first thing we want to educate clients is… how we handle those distressing situations when it happens.

“We go through therapy with them to work through those activating events as we call them. The same goes in high stress situations with scammers,” said the director of People Psychological Solutions, a practice in Kuala Lumpur.

“The most immediate solution is to exit the event altogether because that is when fight or flight is less activated and we begin to recollect our emotions and we can reason much better.”

Breaking the spell

One simple solution to breaking the mental block, Tan said, is to take a break.

“Take five or 10 minutes, take a breather and call the relevant authorities. If the person is calling from the bank, call the bank to double-check. That five or 10 minutes could be life-changing.” he added.

For Ryan*, a phone call from a friend broke the spell.

The young professional is among thousands of Malaysians who fell victim to the ubiquitous “job scam” - one of the top three most common scam, according to the National Anti-Financial Crimes Centre.

Since 2021, RM302 million have been lost to job scammers who mostly target those desperate to make ends meet by offering them a “part-time job”.

Jobless at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, and without any other opportunity to make money, Ryan typed in “part-time jobs” in his Google search bar and found a website offering just that.

He was added to a WhatsApp group where other apparent job-seekers like him were paid sizable commissions for completed tasks.

“The commissions were tempting,” he said, even though the actual task was not clear.

He didn’t interact with the group in any way, and took two weeks before he decided it appeared legitimate enough. He took the bait.

The task involved making “payments” for items advertised on Shopee, but instead of purchasing directly on the e-commerce platform, he had to transfer the funds to provided bank accounts. In return, he would be paid a commission.

“The first three times, I got my money back. I got excited. I thought, ‘I can do this job just to keep afloat.’ I took the bait. After that, the ‘items’ (which I had to pay for) would get more and more expensive,” he said.

Not only were the items more expensive, but the tasks became more complicated and the timeframe provided to complete the tasks shortened to the extent that he would fail to complete them.

Each time, Ryan would take on another task in an effort to recoup the money he had put in. In less than five hours, he lost RM18,000.

He could have lost more. Amid the scam, Ryan received a call from a friend who within seconds of being told what was happening, quickly recognised the telltale of the scam.

“My heart just sank and I felt my whole world darken around me. I remember just thinking, ‘What have I done?’,” he said.

Step by step

Outside of fear and panic, Ryan was manipulated through at least two other tactics often employed by scammers, according to Relate Malaysia, an organisation aimed at raising mental awareness.

Like fight or flight, experts said these tactics are also a manipulation of human tendencies.

“Scammers often manipulate our emotions and desires, like longing for wealth, fear of consequences or need for a connection.

“(They) promise financial gain, play on ‘fear of missing out’ or create time pressures to lure others into complying with their requests,” Relate Malaysia said.

Awareness alone not enough

Teaching people the red flags to watch out for and how to get out could be one way to reduce the prevalence of scams, Akhbar said.

But having studied criminals and their modus operandi for decades, the criminologist believed raising awareness is only part of the equation.

Authorities can do more to plug loopholes which are used by scammers, he said.

In the past few years, the banking and telecommunications industries, as well as law enforcement agencies have rolled out various initiatives to combat scams.

This includes publishing the bank account numbers suspected to be used by scammers to syphon money, setting up a National Scam Response Centre (NSRC) and rolling out nationwide awareness programmes.

Many banks have stopped using the SMS TAC system for online transaction verification and added more “friction” to transactions to halt possible scams.

“But the scammers are always two steps ahead,” Akhbar said.

For example, he said, when the government announced the NSRC, scammers started masquerading as phone operators from the centre to trick victims into thinking they had been scammed.

Data leaks also give scammers the upper hand. In many cases, scammers contact victims and offer information like their address, bank account details and identity card numbers, giving them a sense of legitimacy.

“We need to train more experts in this field within law enforcement and hire more ethical hackers who can help the agencies prevent, intercept, locate and detect scamming syndicates,” Akhbar added.

Key resources hard to find

Further, it appears key resources meant to assist the public from getting scammed are not reaching the masses.

When Marissa* started to feel something was amiss about the cryptocurrency trading firm she had invested in last November, she started frantically trying to search for information online to check if the firm was legitimate.

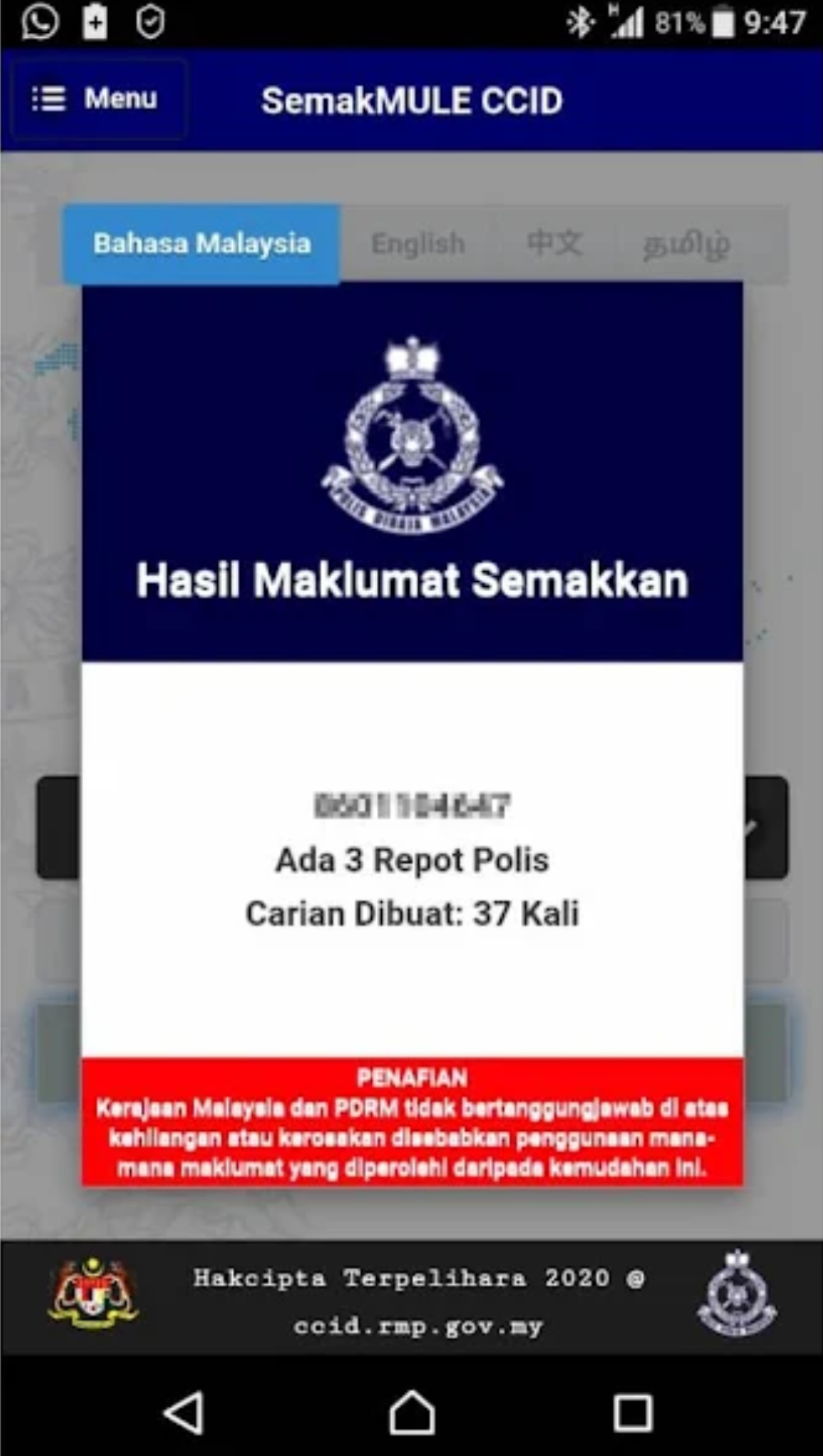

It was only after some days of searching that she found the police’s Semak Mule website. There she discovered that the bank account she had deposited money to had three police reports against it, and was likely a mule account.

She found the information about Semak Mule at the bottom of an old news article reporting on an MP’s press conference held some years ago.

“It was buried deep inside the Google searches. I really had to look hard to find it,” she said.

It was only after that, with some help from friends, she found that the website she had invested in had only been set up just days before she made the first transaction.

But worse, she said, was finding out that the bank account she transferred the funds to was still transacting as normal, even though there were three police reports against it.

As of January this year, 11 police reports had been lodged against the Maybank account and yet it was still transacting. It took about four months for both the bank account and the website to be suspended. Malaysiakini has contacted Maybank for comment.

Endless game of cat and mouse

During a discussion on financial scams last year at Bank Negara Malaysia, enforcement agencies listed various reasons such scams are hard to prosecute and why scammers rarely get arrested.

The answer lies mostly in the complexity of most scams, said National Anti-Financial Crime Centre (NFCC) deputy director Kamal Baharin Omar who is also a public prosecutor.

“When the NSRC receives a complaint from a scam victim, the first thing they do is freeze the bank accounts involved and block the phone numbers,” he said.

But even that cannot be done so quickly, he added.

The Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) which has the power to suspend telecommunication services accounts, first needs evidence that the number was used for scamming to avoid wrongfully suspending the accounts, Kamal explained.

“Layering” of transactions by scammers - where the funds are moved around various bank accounts to mask the financial trail - also makes it harder for financial institutions to move fast.

“When the money allegedly syphoned in a scam co-mingle with other funds in an account, how do we differentiate the funds apart?”

MCMC deputy director Wahidatul 'Abdah Aminul Rashid said scammers are also known for using “mule accounts” - accounts rented from third parties - so it is difficult to finger the perpetrator for prosecution.

The law, too, needs to catch up with technological advancement, she added.

Some scammers rely on “spoofing technology” where phone numbers are masked using applications easily found online.

Using this technology, the caller ID makes it look like the caller is someone known to the individual.

“So I can use this to call someone and ask for money. This technology is illegal, but (because the application is hosted abroad) it is not bound by our law,” she said.

Frustrated by the various challenges in what appears to be an endless cat and mouse game against scamming syndicates, the authorities want the public to take more responsibility.

In the end, she said, the ultimate defence against online and phone scams is the public themselves.

‘I walked him straight to the police, and now he’s free’

But in some cases, refusal to prosecute seems rather baffling.

After months of being caught up in a love scam involving a man she had met online, Sarah*, an entrepreneur in her mid-thirties, managed to not only uncover his real identity but also hand him over to the police.

As she saw him led away in handcuffs, Sarah felt both devastated that she had fallen for a scam and relieved that the scammer would be faced with justice.

In a very lengthy thread in popular web forum Low Yat, many other women claimed they were duped of millions of ringgit by the same person. The scams went back as far as 2019.

But her sense of relief was short-lived. Soon after that, she learnt that her case would not be prosecuted and the man who scammed her had walked free.

Sarah said even during the investigations - which took mere days - the investigating officer had implied that there was no case because she had “willingly” given the scammer the money.

Since then, Sarah’s lawyer had filed an appeal with the Attorney-General’s Chambers, listing a litany of possible charges which could have been filed against the scammer, including charges of cheating.

“(The investigating officer) asked for documents like bank accounts and statements, but within hours of receiving the documents, she sent a message to my lawyer saying the case had been classified as No Further Action (NFA).

“I later found out she obtained CCTV footage of me at the bank with (the scammer), and this was seemingly proof that I was not coerced,” Sarah said.

“It is infuriating. I walked him straight to the police, and now he’s free.”

No closure

Like Sarah, Alex’s mother continues to be shaken by her brush with the Macau scam, even though many years have passed.

Immediately after Alex’s mother lost her savings to a scam, his family lodged a police report providing details of the scammer’s phone number, bank account and the account holder’s name.

Yet, by the time they notified the bank to inform them of what happened, it was too late to stop the transfer. The transaction was cleared within minutes.

Although it has been several years since the incident, Alex and his family still occasionally wonder if the police could have done more to effectively trace these criminals and hold them accountable.

“When I lodged the police report on behalf of my mother, it was only a few hours after the incident happened and I had all the details they needed.

“So were there really constraints from the police side of things or is it because incidents like these happen too often and they are incapable of doing anything about it?” he asked.

This compounded the emotional devastation.

“We never got closure from this,” Alex said.

“It’s not so much the money, but it was the whole traumatic experience she went through. It was how vulnerable she felt at the time and how stupid it made her feel after.

“This is about more than RM20,000. The long-lasting trauma that the victim experiences is so much more than the monetary loss. We don’t talk enough about it,” he added.

*Editor’s Note: Scam survivors’ names have been changed to protect their privacy.

Resources

Before investing, check the scheme's legitimacy:

- Securities Commission registry of authorised digital asset exchange companies

- Bank Negara's list of unauthorised investment companies and websites (This list shows entities which are not authorised and is not exhaustive.)

- Bank Negara’s list of authorised trading platforms

- Bank Negara’s list of authorised financial sector participants

You can also check the website address:

- Webparanoid scam database for potentially dangerous websites

- Tool to see when the website was created (Scam-related websites are often, but not always newly created.)

Before you make any bank transfers:

- Check the recipient bank account number on police’s Semak Mule website

- If the account holder is a company, search for the business information at the Companies Commission database.

Companies linked to scam accounts are often, but not always newly created.

Other resources:

- If someone calls claiming to be from your bank, hang up and verify the details yourself by calling your bank’s 24-hour hotline.You should do the same for other services or agencies, for example, if someone claims to be calling from a courier service or police. Find the phone number for your nearest police station here.

- Learn how to block and report suspicious phone numbers on WhatsApp here.

- Go here to report a scammer who used Telegram, or if someone is impersonating you on Telegram.

- If you believe you have been scammed, call the National Scam Response Centre (NSRC) at 997 (from 8am to 8pm daily)

- Learn about various other scams here.