Climate change is here.

From 1969 to 2009, the temperature in Peninsular Malaysia rose by 1.1 °C, Sabah 1.2 °C and Sarawak 0.6 °C. Simply put, we have been enduring hotter and hotter days.

In the Klang Valley, for example, the number of days when the temperature breaches 32°C is on the rise, according to weather station data maintained by the Meteorological Department.

In 1971, only 176 days - or about half the year - were hotter than 32°C. In 2020, 80 percent of the year surpassed that threshold.

By the end of the century, climate change could push the average temperature in Malaysia up 2°C, modelling by the National Water Research Institute of Malaysia (Nahrim) shows.

But what does that mean for you and me?

The charts below show temperature data captured at the weather station.

Search for your location, to see how the temperature has changed in your area, according to data from the closest weather station.

Rain, floods, and living in fear

When floodwaters started rising in their single- storey home in Taman Melawis, Klang, Parathaman Muthu’s critically ill wife could not hold back her tears. The elderly couple were alone in their home, where they have lived for decades.

Located next to the river, the old residential area would often witness small floods, but this was no ordinary flooding. When the water reached his waist, Parathaman knew he had to act.

“We couldn’t sit there and wait for help. I took a file with our important documents, carried my wife and started walking out.”

Parathaman is a slight man in his mid sixties. That night, in the pouring rain, he trudged a kilometre to the nearest petrol station, with his wife on his back. There, they waited for help.

The couple was among thousands affected by floods that month.

On that day, a month’s worth of rainfall fell over the Klang Valley, rendering all irrigation systems useless. It was worse in Klang. The Department of Irrigation estimated 316.5 mm of rain fell on Klang on December 17, 2021, surpassing the national monthly average.

But what’s that got to do with climate change and rising temperatures?

How much more rain are we expecting because of climate change?

By the end of the 21st century, some regions in Malaysia could see up to 23.6 percent more rainfall, Nahrim projects. Rainfall is also becoming more intense. About 29 percent more water falls within a three-hour rain spell compared to a similar rainy day in the 1970s.

This means existing infrastructures are completely overwhelmed. In various parts of the country, the number of days with intense rainfall is also on the rise.

In the Klang Valley in the 1960s, only three days experienced more than 50mm of rainfall. Last year, 20 days experienced the same. When all of that rain is concentrated in a period of two to four hours, flash floods happen.

Trauma and poverty

Joe Lee lives down the road from Parathaman in Taman Melawis. He believes the drainage system, first built in the 1960s, can no longer withstand the growing development in the area and the intense rain brought on by climate change.

He does not know how much longer his neighbours, many of whom are elderly and have lower income, can continue living in fear.

Usually, he said, his home is spared because he spent money raising the foundations. But that night, water crept up to the bed where his infirm mother slept, while he made sure a python, which washed up with the floodwaters, did not enter their front door.

For months after the event, he would sleep restlessly, waking to check the water levels each time it rained.

Once, startled from sleep at the sound of rain, he rushed to look out the back window to find it wasn’t even raining.

“I was hearing phantom rain.”

Wildlife washed up in the floods made evacuation more dangerous in Taman Melawis, Klang. Video supplied by Taman Melawis residents.

Trauma is usually an unaccounted cost of climate change disasters.

However, the UK Environment Agency’s research has found that exposure to storms and flooding can increase the risk of clinical depression by 50 percent.

It also found that floods often hit lower income households, who are either uninsured or do not have the resources to rebuild, especially after repeated incidents.

Shamala Devi, 53, has lived in Taman Bunga Ros, just a stone’s throw away from Taman Melawis, practically all her life, and inherited the home from her mother. All her money has been sunk into her home.

“Every time we have extra money, we use it to build something for the house to make sure flood water doesn’t come in,” she said, showing the various makeshift bunds and steps.

The latest are two wooden planks, glued to the kitchen door frames about a foot high and make moving in and out of the house difficult.

Still, last December, floodwater gushed into her home, and over bunds and steps, like mini waterfalls. Video supplied by Shamala Devi

On that day, Shamala, her husband and daughter rushed out, hoping for rescue.

“It was completely dark and quiet. No one was around. So my husband said, ‘Okay, let’s go back in.’ In those few minutes, water had already risen half a meter high inside.”

Now, every day, the residents check the tides and when rain coincides with high tide, no one sleeps.

“I will text the man who manages the water gates and ask him if the gate is open, and if it is closed, what time it will open. And then I stay awake until the rain stops.”

When the sea water rises

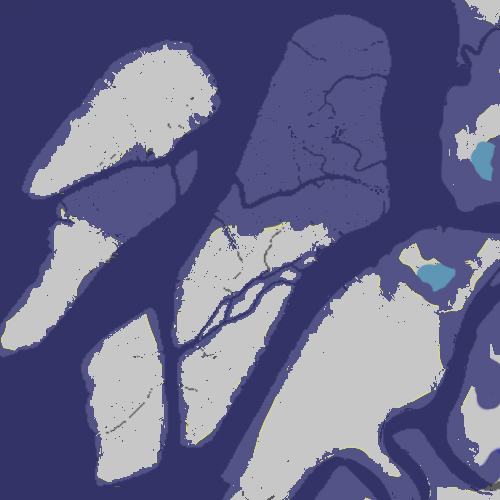

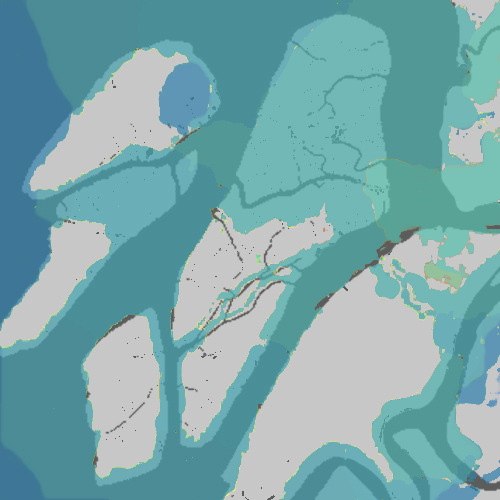

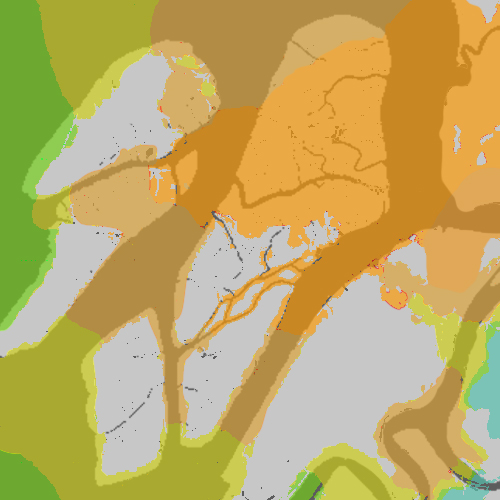

Nahrim researchers project that climate change can place entire villages in coastal and island Klang under water. Their sea-side location means the flooding is compounded by the rise of sea levels - another outcome of climate change.

Extreme rainfall coinciding with high tide can turn residential areas into giant swimming pools, because tidal gates closed to keep sea water out will similarly keep floodwaters in.

In Malaysia, in the worst case scenario, it is projected that sea levels could rise up to 0.74 metres by the end of the century, at a rate of 11mm a year. In the absence of mitigation measures, many low lying areas would be under water.

One such place projected to be completely inundated by the year 2100 is Teluk Gong on the Klang coast, where Musminah Saiman, 53, has lived for about five decades.

“This used to be a beautiful place,” she said, her eyes pooling up in tears.

Projection of flooding due to sea level rise in Klang islands and coast

2.00m

2.85m

Source: Nahrim.

Musminah lives next to her sister, and when Malaysiakini visited, a mound of dirt was piled in between their homes. They had spent more than RM1,000 to buy the soil, in hopes of raising the grounds to stop floodwaters.

Their younger brother, who lived on the other side of their home, had done this before but even he has moved out after multiple floods.

His sisters remain because they cannot afford to move.

“When I think of the damage we endured in December, I can’t believe we managed to clean out everything and that we’re still living here. At the time, I felt like taking a tractor and demolishing the entire home,” Musminah said.

Ruined farmlands and food security

Coastal farmland in Kuala Kedah is vulnerable to rising sea levels. Video by Mukhriz Hazim, Malaysiakini.

Izham Hassan, 51, knows well the economic struggles related to climate change.

In 2016, he was one of 22 farmers in Kuala Kedah whose harvest was ruined due to rising sea levels. That year, the smallholding farmers lost more than half a million ringgit.

“Even now after so many seasons, the yield is poor because the soil has yet to recover from the effect of the salt water.

“We want the government to pay compensation to the affected farmers and now almost six years later we have yet to receive any help from the government,” he said when met at Kampung Padang Garam.

Izham lives next to his paddy field with his four children and is a fourth generation paddy farmer. The 2016 incident was the first time sea water entered their fields.

The farmers fear a recurrence, even though a bund has been built by the authorities in 2020. This is because the bund is made of stacked rocks, and water can still seep through.

Marhayani K Rahim, 42, who was born and bred in the village, owns 16 furlongs of paddy field land but could not harvest anything for years after the incident in 2016.

“We invested RM1,000 per furlong and we planted in five furlongs and there was zero yield. The following four seasons we had zero yield, too.”

Farmers often bear the brunt of climate change, as their business relies on reliable weather patterns. Besides salinity, they also lose hundreds of thousands of ringgit in crops to freak storms and droughts.

Droughts in the Kedah-Perlis plains, where much of Malaysia’s rice is grown, also has a compounding effect. It releases acidity and toxic iron into the soil, worsening rice production.

Changes in temperature and rainfall could cut yield by close to a third, various studies found.

Worse, a survey of the farmers found that most are no longer keen on planting paddy, if climate challenges do not abate.

With Malaysia producing only 70 percent of its rice needs, and currency devaluation making imports costly, this is a recipe for greater food insecurity, affecting all Malaysians.

A climate emergency

The bund built to stop sea water from entering paddy fields in Kuala Kedah in 2020 have thus far been successful but it did not come cheap and will not last forever.

A similar bund in Telok Gong could not stop water from inundating villages last year, while in Taman Bunga Ros and Taman Melawis, the Selangor government is spending more than RM20 million on ongoing flood mitigation projects.

“What we need is for the state of Selangor to declare a climate emergency so more can be done for Klang and other coastal areas of Selangor, with greater urgency,” said Klang MP Charles Santiago.

“The concern is that this will cost money, but we don’t need to do everything at once. For example, we need to rethink the drainage and irrigation in Klang.”

Nahrim projects that when sea levels rise, due to climate change, an area the size of 5,600 football fields in Klang will be underwater. A sizeable portion will be the industries in Port Klang.

If the plight of residents does not move the needle, Charles hopes the government can consider the economic impact of the floods, including businesses utilising Port Klang.

Last December, he said, the floods meant microchips coming into Port Klang could not be processed, causing delays in manufacturing of cars meant for export to the United States.

Further problems at the ports in Klang could lead Malaysia losing more business to Singapore, he added.

The Klang MP said factory owners in Teluk Gong told him in the past six months, they endured floods of up to three feet -- twice when it was not even raining, because of rising tides.

“Although sea level rise projects may seem mild on paper, the speed of which the sea rises depends on how fast the glaciers melt. So the government needs to be more proactive.”

On a national level, however, Environment and Water Minister Tuan Ibrahim Tuan Man said there is no need to declare a climate emergency.

While acknowledging that climate change has resulted in more floods, he said the government has put in place short-term and long-term plans to both deal with floods and mitigate the impacts of climate change.

He added the country will also commit to measures to reduce greenhouse gases to achieve net-zero by 2050.

As policymakers debate whether or not to declare an emergency, Taman Melawis residents are raising funds to buy inflatable dinghies in anticipation of another mega flood this year.

In Telok Gong, Musminah and her sister continue to spend sleepless nights fearing another climate disaster.

“But this is our heritage land. We cannot afford to move away, no matter how traumatised we are.”