Under the scorching afternoon sun, pineapple farmer Abdul Rahman Amat wipes his sweat from his brow as he harvests a pineapple with a machete.

His farm, just 5km north of the growing data centre hub Sedenak Tech Park, has been his livelihood for more than a decade.

The peat soil of the pineapple plot shifts slightly when walked on. It’s firm, yet plump.

Pineapple farmer Abdul Rahman Amat on his farm

Rahman relies on drain water and groundwater to sustain his 11-acre (4.45ha) pineapple farm in Johor’s Pontian district, where he cultivates two varieties, including the famously sweet MD2.

Despite the rapid construction of data centres further up the road, he hasn’t considered their impact on his crops. When asked if he knows how data centres use water, he hesitates.

“I know they need electricity, but water? I’m not sure how that works,” he said, adjusting his cap.

Every time someone uses the search engine and artificial intelligence tool, or makes an online purchase, that data is stored in a data centre.

On the outside, they look like large industrial boxes with no windows.

Within them are rows of computer servers that need water-intensive cooling systems to prevent overheating. If not properly cooled, servers will overheat and systems fail.

This makes them thirsty buildings.

It is estimated that a data centre with a 100-megawatt capacity uses about 1.5 billion litres of water annually. Stacked up in one-litre cubes, that’s taller than the Petronas Twin Towers (KLCC).

The Sedenak Tech Park itself spans 745 acres, with a 300-megawatt capacity. But for now, Rahman remains neutral.

“Unless something big happens, I don’t think my farm will be impacted,” he said.

With the rise of artificial intelligence and machine learning, global tech giants are vying for cheaper land and resources around the world to build their data centres.

Since Singapore imposed a temporary halt on new data centres in 2019 due to power and land constraints, many major developments were redirected to Johor. The moratorium was lifted in 2022.

Last year, Malaysia attracted RM141.7 billion in investments from companies like Microsoft, Nvidia, and ByteDance, promising high-value job opportunities for locals.

According to government data, these digital investments created 41,078 job opportunities in the first 10 months of 2024.

Johor is the fastest-growing data centre hub in Southeast Asia, according to the think tank DC Byte, which specialises in market insights and analysis on data centres.

Its capacity is on track to reach 1.6 gigawatts of data centre capacity by 2024 and is projected to rise to 2.6 gigawatts by 2027.

Today, Johor has pulled in 72 data centres, with at least 13 already up and running.

But some experts argue the economic benefits are overstated.

Data centres may be overpromising economic growth and job creation, but the reality might be far less impressive, said Alex de Vries, founder of Digiconomist, a research firm analysing emerging technologies.

In Sweden, Facebook’s data centre promised to create 30,000 new jobs…

…but ultimately only employed 56 people to maintain its servers, he said.

“They don’t deliver on promises made - jobs and economic activity,” de Vries said. “(But) the reality is they don’t contribute much.”

De Vries said that in the data centre industry, construction jobs see a short-term boost, but long-term employment is minimal.

“You’re pouring money into an industry that might not return the investment,” he said, adding that unlike other industries, data centres don’t drive additional economic activity since other businesses don’t rely on data centres for good business.

On top of that, de Vries said industries like data centres use huge amounts of resources that could have been channelled elsewhere.

Others, like former deputy international trade and industry minister Ong Kian Ming, believe the spillovers and multiplier effects are worth the investments, if policies are put in place properly.

Attracting megafirms like Alphabet (Google) would also mean a chance to “pitch Malaysia” as an investment destination to the global industry leaders, he said, and expose them to the country’s digital economy landscape.

It also provides opportunities for local players like AIMS, YTL and VADS to expand their footprint beyond Malaysia, he said in a recent opinion editorial.

A policy that incentivises domestic partnerships, including for constructing the data centres, could also mean spillovers to the construction industry, Ong said.

“I disagree with the general viewpoint that data centres will provide only limited upside in terms of job creation and will only use up much-needed and scarce energy and water resources in the country,” he said.

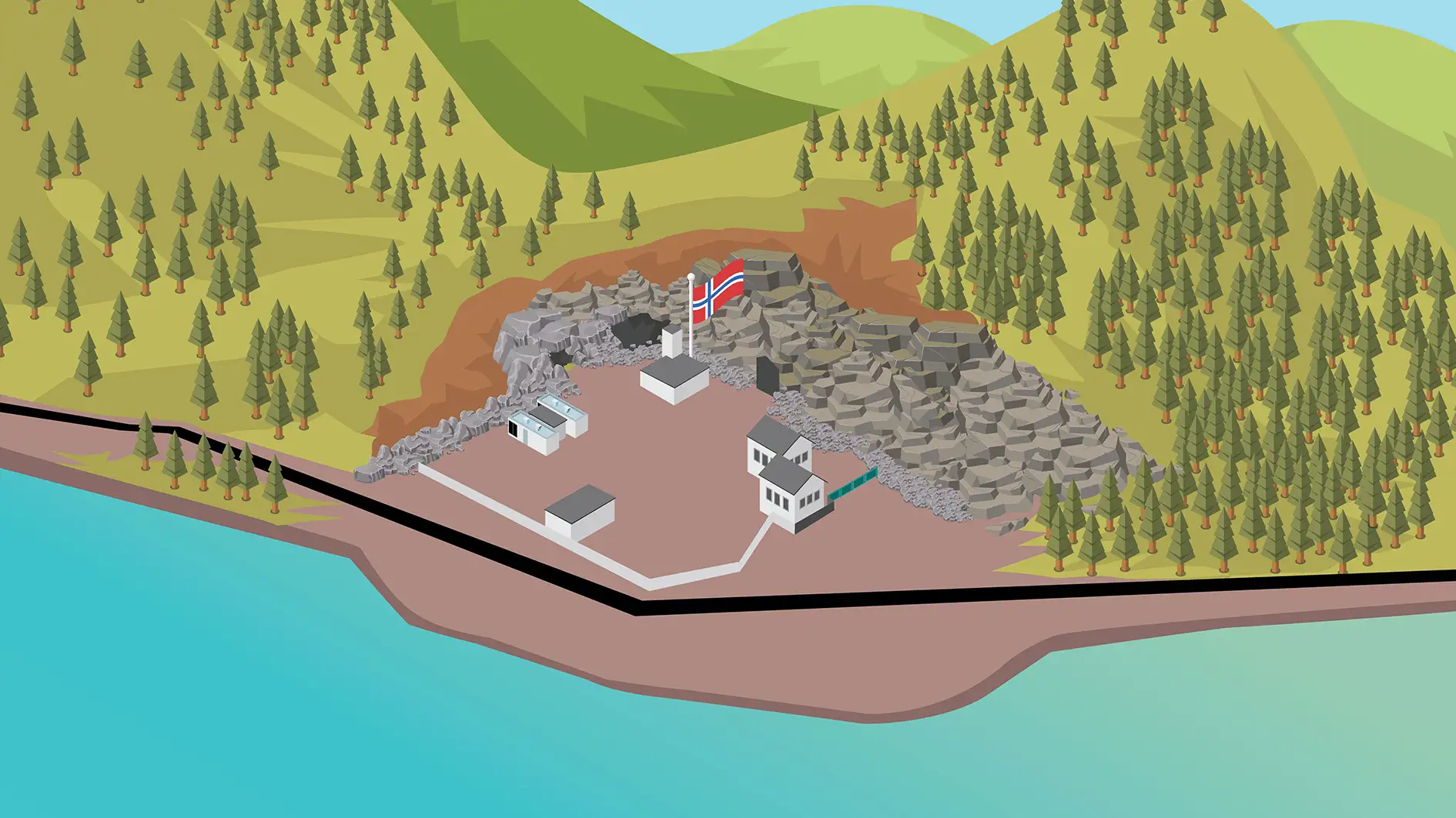

Hover/click on the buildings to see details of the data centres.

Spillover effects notwithstanding, the impact of data centres on water supply in Johor remains a concern not fully addressed.

This is especially as the Malaysian Meteorological Department warns that Asia is warming faster than the global average, with Johor expected to face droughts as early as 2025 and 2026.

As it is, Malaysia’s hot climate forces data centres here to use more water to cool down.

As of 2024, the government received 101 applications for data centre development, which together require more than 808 million litres of water per day.

However, only 45 of those applications were approved, bringing the water demand down to 142 million litres a day - enough to supply the daily needs of more than half a million domestic users.

Despite this, data centres in Malaysia continue to rely on the public water supply - the same source used for drinking and cooking - to cool their servers.

As risks of dry spells become more apparent, the National Water Services Commission (Span) said good water management is crucial.

Its then-chairperson, Charles Santiago, warned that data centres' reliance on treated water for cooling their systems will become unsustainable within three to five years.

This means the transition to alternative cooling methods must happen within three to five years, he said at a data centre conference earlier this year.

Charles, whose term as Span chairperson ended in May, suggested reclaimed water, advanced cooling technologies, rainwater harvesting, and recirculation systems as viable solutions.

Span has also suggested limiting the number of hyperscale data centres (HDCs), which can consume more than 15 million litres of water per day.

HDCs are data centre facilities that store at least 5,000 servers and 10,000 square feet (929 square metres). Johor has 30 hyperscale sites.

With data centres consuming as much water as a small city every day, Johor’s water supply is a vital resource. Now, one of the industry’s biggest players has taken control of it.

Ranhill Utilities Bhd, through its subsidiary Ranhill SAJ Sdn Bhd, operates all 46 of Johor’s water treatment plants.

In July 2024, YTL Power - developer of the YTL Green Data Centre in Kulai - secured a controlling stake in Ranhill Utilities.

With a major data centre player now in control of Johor’s water supply, some stakeholders worry about industrial and commercial users. In particular, whether data centres could receive priority over households and farmers during a pinch.

When contacted, YTL Power declined to comment, while Ranhill was unavailable for a response.

YTL Power’s move to secure a controlling stake in Ranhill Utilities foreshadows what experts are warning against: intensifying competition for water during droughts.

Yet, despite the push to turn Malaysia into a “data centre powerhouse”, there is still not a single regulation mandating sustainable practices for the industry.

Investment, Trade and Industry Minister Tengku Zafrul Abdul Aziz told the Associated Press that efficiency guidelines for data centres are in the works, while there is already a policy for the centres to buy clean energy from producers. None of these is mandatory.

Energy-efficient building expert Tang Chee Khoay stresses that data centre expansion cannot come at the expense of public water access.

Although there are a few guidelines in place to steer sustainable data centre development, he said these guidelines fall short or lack enforceable best practices for drought resilience.

“It’s only effective if companies choose to adopt it,” he said.

“Without government mandates, data centres can continue to operate without any contingencies for droughts.”

One example of a drought contingency plan, he noted, would be for data centres to share the burden of cutting back water usage when residents are asked to ration water.

How much energy and water do you use?

Here are some common actions on the internet. Guess how much energy and water they consume by moving the slider left to right.

Streaming one hour of HD video

🥄 = 1 spoonful of water

📱 = 1 full iPhone charge

Data centres have a reputation for guzzling water and energy, but they don’t have to.

One example is the Lefdal Mine Data Centre in Norway, built inside a former mine next to a fjord, and considered one of the greenest data centres in the world.

Its location allows it to pump the fjord’s 8°C water directly into a closed circuit under a raised floor, allowing for heat exchange.

Within them are rows of computer servers that need water-intensive cooling systems to prevent overheating. If not properly cooled, servers will overheat and systems fail.

This circular solution, however, is less suitable in tropical Malaysia, where temperatures are between 21°C and 32°C on average. Instead, in warmer climates, the approach has been to shift from draining the taps for millions of litres of clean water.

In place, some data centres use alternatives like recycled wastewater, seawater, or even liquid immersion cooling - this involves dunking servers in special fluids to keep them cool.

Malaysia has yet to see these sustainable data centres in operation, but some are expected to be running later this year.

In Selangor, state water services provider Air Selangor has offered to help data centres use sewage water from treatment plants or wastewater from nearby factories.

In Johor, two data centres are exploring ways to use sewage water and direct river intake to reduce reliance on potable water, said state exco member Lee Ting Han.

"We expect more to follow suit, as two other centres have expressed interest in it,” he was quoted by The Star as saying.

Next door at the National University of Singapore, innovation in cooling methods is also being tested in the university’s data centre, built solely as a testing laboratory.

New methods, such as using outside air and evaporative cooling techniques, including Meta’s StatePoint Liquid Cooling unit, are being tested for their ability to perform in warmer climates.

Like Meta, Tang said, most big players are already taking the sustainability question seriously, anticipating a demand from their clients in the next few years.

He noted that while large hyperscalers often implement their own sustainability measures, smaller data centres require stronger regulatory incentives to operate sustainably.

Zayana Zaikariah, a researcher at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies studying the environmental impact of data centres, agrees.

She noted that large, smaller or newer operators may not meet the same benchmarks as larger, publicly listed operators in sustainability measures.

“The challenge is in ensuring consistent compliance,” she said. “Small players may fall through the cracks, particularly where enforcement is weak or regulations are voluntary.”

Tang is developing the Green Building Index Data Centre New Construction (GBI DNDC) Tool, which scores data centres on sustainability measures, including water efficiency and drought contingency plans.

However, the certification remains voluntary.

While existing water reserves may seem sufficient, he said extreme weather events will pit industries, households, and data centres against each other.

“Once there is a drought, everyone will be fighting for water,” he warned. “The data centres are not going to shut down, so how?”

“Everyone wants the internet, so it’s a matter of developing our data centres sustainably.”

Credits

Researcher, writer and photographer:

Ashley Yeong

Editor and Project Coordinator:

Aidila Razak

Sub-editor:

Melissa Darlyne Chow

Illustrator and Designer:

Amin Landak

Web developer:

Support:

This project was supported by the Earth Journalism Network.