This harrowing story of a stateless woman having her child snatched away is not unique.

Malaysiakini documented three other similar cases.

Two of the mothers regained custody of their babies while another mother, faced with the prospect of losing custody, was found dead with her child, having committed murder-suicide at the hospital.

Advertisement

Accused of neglect

Aimah’s ordeal began in September 2021, when she was rushed to the hospital with her premature baby, following an unexpected home birth.

Mother and baby, on the brink of death, were warded immediately. Aimah recovered in a few days after a blood transfusion and was asked to go home while her baby recovered in the NICU.

“I had to care for my other children at home. I am still breastfeeding some of them,” she told Malaysiakini, via a translator.

A child protection officer representing the Welfare Department accused Aimah of child neglect, after the baby was in the NICU for about two months.

Although her baby was not ready to be discharged, Aimah rushed back upon hearing of an imminent adoption order relating to her baby.

Within one week, the officer processed the application and the Magistrate’s Court granted the adoptive parents custody of Aimah’s baby.

The Bajau Laut are sea nomads living on the open waters and their ancestral maritime domain stretches across the Sulu-Celebes seas between the island of Borneo and the Philippines.

They have been faring between sea villages in Sulu in the Philippines, Semporna in East Sabah, and South Sulawesi in Indonesia, for generations.

Despite being recognised by the Sabah government as indigenous people of the state, most of the Bajau Laut community are stateless by law, and are often hounded by the Immigration Department for being “illegal immigrants”.

This bars them from seeking any avenue of redress and attempting to make a police report would risk their freedom with a potential indefinite term of detention at Sabah’s infamous Rumah Merah detention centres.

Without government-issued documentation, these stateless communities are prevented from getting formal jobs, protection by labour laws, education, healthcare, and are pushed to the brink of survival.

They are recognised by their preference of being barefoot wherever they go, and are shunned by many Sabahans as people from the lowest stratum of human beings.

The few who secure ‘cash-in-hand’ jobs earn less than half of what their colleagues who are citizens will take home.

Those who depend on the sea for a livelihood have to settle for less as seafood wholesalers peg a lower value on anything they catch.

Aimah’s husband, stateless and penniless, was detained before the birth of his youngest child and remains in detention, unqualified to be deported to any country.

He has not received the news that they have lost custody of his youngest child - a child he has not met.

Repeated incidents of stateless mothers losing custody of their babies in Lahad Datu Hospital have struck fear among expectant mothers and those with young children, discouraging them from seeking medical care for themselves and their children.

This new fear has led to one in four Bajau Laut mothers opting for home births, said the village midwife, Fatimah Rafily Darao.

This, on top of the obligation for non-citizens to pay high registration fees and upfront costs of treatment and diagnostic tests, as well as badgering from hospital administrators if fees cannot be paid.

Against United Nations recommendations, stateless patients in public hospitals are charged the same fees as foreigners, starting with a RM100 upfront registration fee and RM120 outpatient clinic fee.

To avoid hospital staff harassment for payments, many stateless persons bear with the pain and wait until they are in critical condition with the hopes of being accepted into the Red Zone in the Emergency Department – the only place where all upfront payments are temporarily waived.

Sometimes, they wait too long and suffer irreparable damage or die.

Advertisement

Adoption process halted upon threat of a counterclaim

Kampung Panji village head Fandry Alsao said apart from Aimah and Arung, two other stateless mothers from his village almost lost custody of their babies in similar circumstances.

But Fandry’s timely intervention prevented this from happening. In these cases, he said, the child protection officer relented after Fandry threatened to “file a counterclaim (tuntut)” for custody of the child.

“These words seemed to shake the officer,” he said.

He said all cases, except Arung’s, involved the same child protection officer.

In all the cases documented by Malaysiakini, the mothers said they were unable to go to the hospital every day because they had other children to care for at home.

And while they were away from the hospital, in just a matter of weeks, a prospective adoptive parent was introduced as a carer for their respective babies.

Stateless mothers deemed unfit

Apart from Sarlina, all four mothers were accused of neglect or being unfit parents when custody of their infants came into question.

When it came to teen mothers, the same child protection officer with the Welfare Department told Malaysiakini that underaged mothers were automatically deemed unfit because of their age and because they were not legally married.

The officer was transferred to Lahad Datu sometime in early 2020, and was not involved in Arung’s case.

“A girl aged 16 years old is not mature enough to take care of a child. But if she was legally married (status nikah yang sah), then it is not an issue,” he told Malaysiakini.

Citizen or not?

Not all babies born in Malaysia are citizens. See if you can tell which baby is a citizen and who isn’t.

Question: 1 / 8

Score: 0

A baby is born to a married couple. Only one parent is Malaysian. Is the baby a Malaysian citizen?

He said in Sabah, underaged girls who want to marry must seek permission of the Syariah Court if she is Muslim. If she is deemed mature enough, she can marry.

As such, a registered marriage is proof that a teenager is ready to be a mother, he said.

The child protection officer, who acted in all the cases except for teen mother Arung’s, said he generally viewed the stateless community to be unfit parents.

This is because they live in poverty and deplorable conditions, which he said is unsuitable for a child.

While Bajau Laut men earn their keep by doing odd jobs, the officer claimed the women often took their children to the streets to beg, just for the fun of it.

“I have been to many places in Sabah and street beggars are not a big issue in places like Kunak and Semporna.

“Begging for money is not their sole option, especially in Kunak where all the (stateless) are employed,” he said.

Swift adoption process

There is no direct evidence that Bajau Laut babies born to stateless mothers are being targeted for adoption, but the swiftness of the adoption process raises questions.

The legal adoption process in Malaysia is known to take years and in March this year, Women, Family, and Community Development Minister Nancy Shukri announced a stricter selection process for adoptive parents when she launched new guidelines for eligibility.

It was reported that the new selection process would involve a psychological measurement tool designed to provide scientific data on an individual’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviour.

The process of child placement would be overseen by the respective state Social Welfare directors.

The stricter processes in place suggested longer waits and greater safeguards for adoptions but they do little to reassure stateless mothers who are wary of taking their young children for treatment in hospitals, especially without avenues of redress should anything untoward happen.

Who paid the hospital bills?

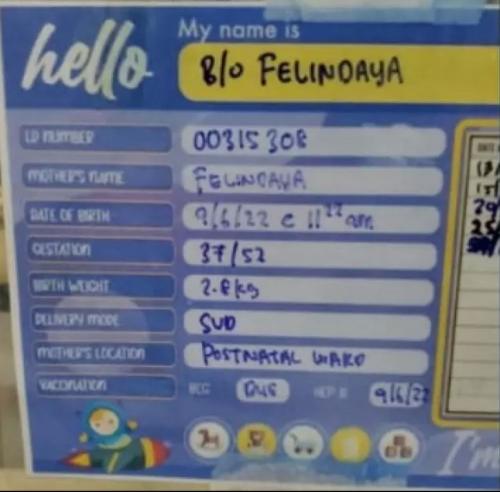

Curiously, the three mothers who spoke to Malaysiakini were not badgered to settle hefty bills for their babies’ care in NICU - something uncharacteristic of the Lahad Datu Hospital’s revenue department which reportedly collects bills from non-citizens with zeal.

Sarlina only paid RM50 but treatment for a non-Malaysian baby in the NICU alone would have exceeded RM10,000, those in the know tell Malaysiakini.

A medical official from the hospital, who spoke on condition of anonymity, estimated Felindaya’s bill to reach RM50,000 but she was allowed to leave the hospital without harassment for the full settlement of her bill.

“Aimah was not asked to settle her bill but that could be because she no longer had custody of her baby,” said the medical official, who was unsure if the bill was settled by the adoptive parents.

A Bajau Laut woman bringing clean water to her home.

No records

Medical officials from different parts of Sabah who spoke to Malaysiakini said hospitals don't have to keep records of the stateless individuals they turned away.

“So, even if they wanted to complain about the death of a loved one as a result of being turned away by the hospital, they can’t because they are not on our records,” one medical official in Kota Kinabalu said.

The hospital, however, keeps a record of all cases treated at the hospital in the form of 'case notes' like a repository of patient medical history, accessible with the consent of the revenue department.

An unforgettable case was of a child who was held under observation for 12 hours and sent home with her fatal injuries untreated because her father was unable to raise the funds needed to conduct the surgery that would have saved her life, the healthcare professional said.

A Bajau Laut child climbing into his home.

Unlike other cases of stateless patients, Arung’s death was high profile, and was investigated not just internally but also by the police.

But questions arose when the staff nurse, who conducted the internal hospital investigation, was transferred to Tuaran Hospital less than a month after the incident, after serving more than a decade in Lahad Datu.

The then Lahad Datu police district chief Nasri Mansor who, on the day of the incident vowed to the media to find out the real reason for the tragedy, has since been transferred out of the state to Bukit Aman.

The district crime team has declined to comment.

Malaysiakini has contacted the women, family, and community development minister and the Health Ministry, and is awaiting their response.

The Sabah Health Department, in a statement after this article was published, denied there were any cases of baby snatching in public hospitals in the state.

They have also lodged a police report over the matter.

‘Is this my punishment?’

Many of the Bajau Laut are not proficient in Bahasa Malaysia because they do not have access to formal education and have little interaction with those who speak the language.

Despite this, Aimah has helped close to 100 fellow stateless villagers in critical condition to the hospital’s emergency department, in hopes of being admitted to the Red Zone, where fees for non-citizens are temporarily waived.

She is their go-to person because after 100 times, she is very familiar with the process.

“I am always scared when I go to the hospital. I am terrified they will call the police.”

She knows she is a familiar face to the hospital revenue department, who she believes is unhappy about her bringing in the stateless patients who cannot pay their bills.

As such, she wonders if having her child taken away was a form of punishment.

Scarred by the incident, she will not return to the hospital - not even to bring a critically ill fellow villager like she did before.

Advertisement

No way to prove the baby is hers

Months after her baby was taken away, Aimah still hopes there is a way for her to regain custody. But she doesn’t know how.

Aimah has no documentation of the birth of her youngest child, and is terrified of lodging a police report because of her own undocumented status.

“If I am arrested, what will happen to my children?” she asked.

Confirming her fears, the child protection officer said the adoption procedure is already complete and during the process, the department, with the help of police, spent a week looking for her.

He said they failed to find her and her absenteeism was reported to the Magistrate’s Court, which handled the adoption.

“Now she has to prove that the child is hers. What proof does she have?” he asked.

He claimed Aimah only showed up after the court had awarded custody to the adoptive parents.

“We already had an application to adopt the child, so we presented the case in court.

“Why not give the baby to a guardian who is legal?”

Editor’s note: The article has been amended to state that Aimah's child was born in September 2021 and not September 2022 as earlier reported. The error is regretted.

Part 2:Stateless boy with HIV dies after being deprived treatment for years.

Part 3:Mounting hospital bills led to stateless mother-infant murder-suicide in Sabah.

Part 4:Toddler’s death by croc attack shows tragic fate of the stateless

Part 5:Generations living in landfill, Sabah stateless may soon face eviction

Part 6:Suhakam: Lahad Datu Hospital under pressure, doing its best