This is a Kini News Lab project

If you like our work, please consider giving a small donation as a token of appreciation so that we can do more projects like this.

Special Report

63 years after Merdeka,

Malaysian children attend camp to learn how to be friends

Written by Aidila Razak and Kow Gah Chie, 21 April 2020

- Loading audioKarthikreyan, 16

- Loading audioYaasin, 14

- Loading audioChai Yi Ning, 17

- Loading audioAmeera Sofya, 14

On a Friday night, in an Islamic secondary school, in the suburb of Bangi, Selangor last December, a group of Malaysian teenagers embarked on an adventure unlike anything they have done in their lives.

The students gathered from various walks of life - some are children of single mothers, some are of mixed parentage. Some live in the Klang Valley, their parents dropping them off. Others arrived by chartered bus, from their hostels from a neighbouring state.

Most have one thing in common - they came from schools that are monoethnic or mono-religious. For most of them, this will be the first time they will be making friends with peers from other ethnicities.

In the next two days, they will learn how. Welcome to Kem Muhibah.

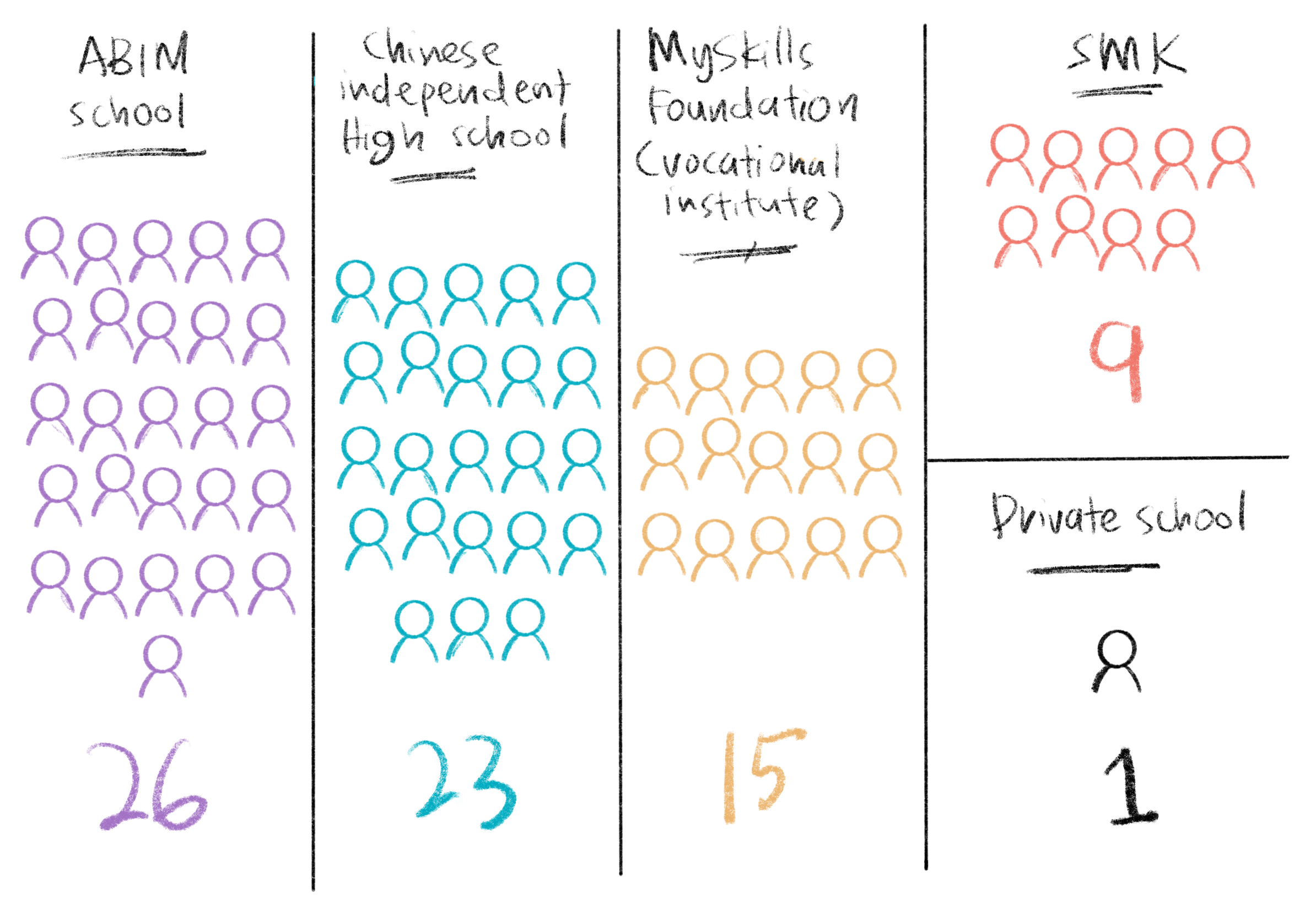

The 77 Kem Muhibah participants are aged 14 and 17, and come largely from three groups. They attend either an Islamic school, a Chinese independent high school or a vocational institution where most of the students are ethnic Indians.

The camp, hosted at Sekolah Menengah Islam Abim, gives them a chance to experience the wonder of multi-ethnic and diverse Malaysia, if only temporarily.

“This a temporary magical space that will only exist for two days, but they can come out of it spending their real lives as individuals willing to explore Malaysia.

“It is hard when you live in a monoracial environment, go to a mono-religious school or your neighbourhood only speaks one language and only has one race, then you don’t have chances to step out of the identity and explore different parts, not only of yourself but of other people,” lead facilitator Jason Wee of the NGO, Architects of Diversity (AOD), said.

Program Partners

That Kem Muhibah came to be is a feat on its own. It brings together community groups often perceived to be at separate ends of fractious identity politics in Malaysia.

Abim represents Muslims/Malays, while Dong Zong represents the views of the vernacular-educated Chinese community. In the wider society, both are seen on opposite ends of the spectrum.

At the time of the camp, national debate raged on regarding the teaching of Jawi in Bahasa Malaysia subjects, with Dong Zong taking a strong stance against it. But at Kem Muhibah, this debate seemed far away. The common goal, instead, was to learn to live together.

“We want them to know although they have differences, this is not an obstacle for them to come together and to reach out to each other.

“We don’t provide answers for them but we guide them through from the discussion and interaction, you can see the answers come from communication, mutual understanding and from here we can build the country together,” Kong Wee Cheng, a Dong Zong representative, said.

AOD, which does the heavy lifting of delivering the challenging curriculum during the camp, sits somewhat in the middle between the two groups.

Like AOD, in between the three large groups of participants was a small cluster of students who attend national secondary schools (SMK) and a private school, which have a more diverse student population.

And through them, the in-betweeners, the conversation began.

How do you start having a conversation about the differences and similarities that bind us?

Where they chose to sit at the beginning of the camp was a picture of the lines that divide us. On one side were girls, the other side boys. And within those groups, they sat with their ethnic groups, with their schoolmates - together in one hall, but still apart.

Soon, they are forced to get out of their comfort zones and assigned to sit in smaller (diverse) groups apart from their schoolmates. This was where the story starts.

The first point of order was to formulate a camp covenant - an agreement on how they will treat each other for the next two days.

In one group, one Malay girl mentioned how she felt uncomfortable after a Chinese boy accidentally touched her hand. In Islam, it is forbidden for opposite genders who are not related to touch, the Sekolah Menengah Agama Hulu Langat student explained.

But she was quick to add that the boy did not know this, and she did not blame him. The group discussed what was permissible and not permissible. They write down “Respect each other’s religion” as a group rule.

In another group, one Malay boy wondered if his non-Muslim friends were comfortable sleeping in a room with many Quranic verses on the wall. He explained what they mean to them. His new friends told him it’s actually not a problem.

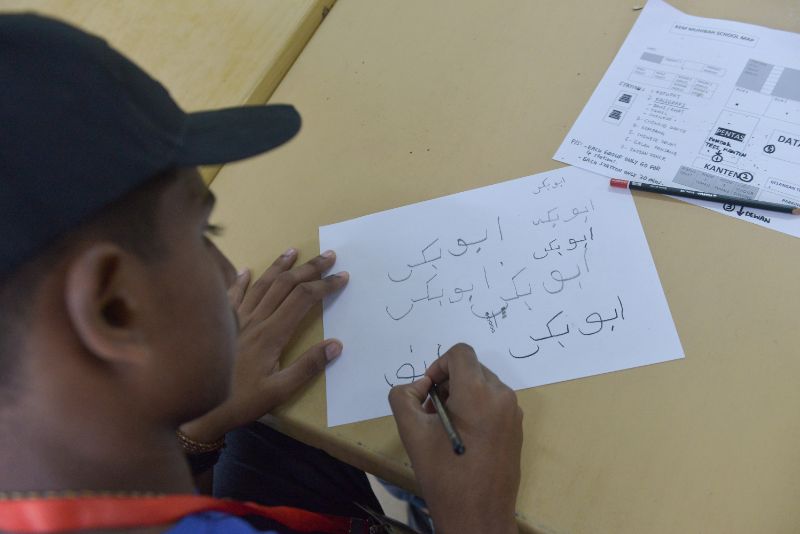

Religion may have been an early differential factor, but the activity in fact posed a bigger challenge - they did not have a common language.

Facilitators do double time, translating between the students who ironically, are trilingual.

All the students have had years of lessons of English and Bahasa Malaysia, and also know Arabic, Mandarin and Tamil respectively. And yet, not everyone speaks English or Bahasa Malaysia - their common languages - at the same level. On the first night, some students just ended up lost.

Finally, one group decided a rule: “We use a language that everyone understands.”

It is easier said than done - but they were willing to try.

The varying levels of fluency in English and Bahasa Malaysia were indeed a challenge - all instructions had to be translated between the two languages plus Mandarin and Tamil when necessary. It also determined how friendships were forged.

At lunch, when the participants were free to choose who to sit with, school and ethnic groupings continued to be formed even until the last day of camp.

One exception was a group of about half a dozen girls from various ethnicities. Most came from national secondary school, but some were from Chinese independent school and Sekolah Menengah Agama.

Hanis Naqeebah Hasri, 15, was among them. At night, she shared, her Chinese roommates asked her questions about Islam - why she woke up before dawn to pray, why she wears a hijab and about fasting during Ramadan. She was their first Malay and Muslim friend, and vice versa.

But mostly, she said, they gossiped about Korean celebrities and taught each other dance moves.

Beyond K-Pop, however, was another common thread. All of them spoke fluent English.

‘I became aware of my ethnicity at the age of 5’

There is a tendency to believe that children are oblivious to race or religion. But in the exercises conducted, the participants revealed they see such identifiers as very much part of their identities.

Arvin recalled how he first realised his ethnicity when he went to kindergarten at aged five. At the time he could only speak Tamil, and couldn’t communicate with his classmates or teachers. It was when he realised he was Indian, and different.

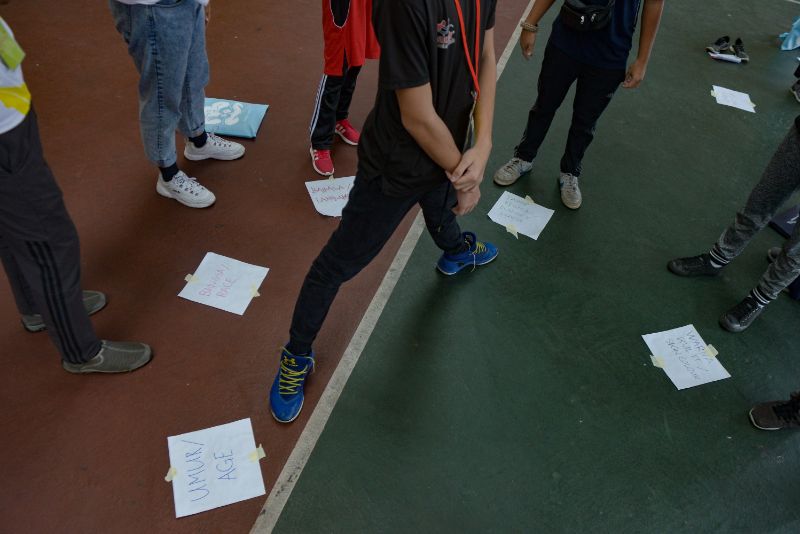

Asked to list five things about themselves, most wrote their ethnicities, religion, and gender - some write nationality and a few write about their families.

“I am a big brother,” one wrote, while another wrote, “I like football”.

They used the piece of paper, which they displayed on their chest, like business cards to introduce themselves to one another. The football fans found one another. Faaris Geoffrey Chapman, who wrote down that he is half Malaysian and half American, gets attention from some curious others who want to know what that means.

The small hall where the activity took place echoed with chatter. Sometimes, facilitators were roped in to help translate, but mostly the participants were bridging communication barriers themselves.

Yohan Sivakumar, who attends the vocational institute, approached a group of Chinese boys and started conversing in Mandarin. They are elated to learn he can speak their language. Yohan introduced his friends from his school and helped translate between them. For the Chinese boys, this was the first time they’re speaking with an Indian boy their age.

Aden Tan is a 17-year-old boy who attends a Chinese independent high school. He is well-read and abreast with current affairs. Unprompted, he talked about the United Examination Certification (UEC) issue and the Jawi dispute as things which are important to him.

He has been reading the news since he was in primary school and he believes it has affected how he views other races.

But in this camp, he shared, he has found a Malay girl who is academically advanced. She is only 15, but will sit the SPM examinations soon, a year ahead of most of the nation. It lights up a bulb in his mind.

“I think we should stop stereotyping that the Chinese are better and Malays are lazy,” he said.

“After communicating with them (Malays), I feel they are like us. Some work as hard as us in their studies and some of them face misunderstandings like us,” he said.

His view was echoed by other Chinese teens. One shared: “We are taught by the elders that Malays are poorer and we Chinese have a higher social status.”

Tan said this experience has taught him that in the future, when he reads news which paint other races in a negative light, he will take time to consider before forming an opinion.

Negotiating our different needs

As far as unfavourable views go, it’s certainly not a one-way street.

Muhammad Yaasin al-Hakim Muhammad Suhaimi is a 14-year-old Malay boy who attends the Abim school.

He was encouraged to join the camp by his mother and teachers as a practice run, because in the following year, Yaasin’s family plans to move and he will have to enrol in a more diverse national secondary school.

“Before this, I always thought Chinese people were always trying to take our rights (as Malays or Muslims),” he told Malaysiakini.

In his neighbourhood, he shared, there was a Chinese person who complained that the azan (Muslim call to prayer) was too loud. Yaasin found this insensitive - the call for prayer is a crucial part of his life as a Muslim.

But in fact, he admitted, he was not sure if the complaint came from a Chinese neighbour, or even if it happened in his neighbourhood at all. It was just something he heard, yet it left a bad impression in his mind.

Malaysiakini’s conversation with Yaasin took place after participants successfully completed what was one of the most challenging tasks of the camp - the earthquake game.

In this game, they are given a scenario - The world was destroyed in an earthquake and they are the only survivors. Their task is to rebuild the world, starting with a state constitution. Each group gets a set of rules and beliefs.

To win, the participants must get as many of the rules from their own group into the constitution. But they are set up to fail. Their rules contradict with rules held by other groups.

It is a simulation of society at large - how do we negotiate middle grounds, without sacrificing our own beliefs.

Reflecting on the earthquake exercise, Yaasin felt he could have acted differently upon hearing the azan rumour.

“I don’t feel like they (the Chinese) just want to take what’s ours anymore. If this happened again (the rumour on the azan), I would ask them why they don’t want the azan, and understand their reasoning first,” he said.

The words Yaasin chose still showed a division between “us” and “them”, “ours” and “theirs”, but Wee said this is not necessarily a bad thing. In fact, this is the goal of the camp.

“I don’t like the word unity, I prefer the word diversity. Unity is a picture of ‘we are all the same’.

“As a community, we will always have irreconcilable differences, but it is the skill set of finding out why you have that preference and coming to terms with that (is that is important). To ask that question - there needs to be differentiation first," Wee said.

In psychological terms, Wee added, what Yaasin described is “perspective-taking” where he recognises there are differences, but is able to consider the different position. The participants’ progress in this area is carefully measured.

A public policy student, Wee is working with social psychologist Ananthi Al Ramiah to measure if the students’ perceptions of other races have changed, and whether these changes endure once they return to their home environments.

To do so, the participants have to answer a questionnaire modelled on a similar study conducted by Ananthi and her colleagues in 2017 when adults in Peninsular Malaysia answered questions to measure their perception of other Malaysians, and their levels of interaction.

But unlike respondents of the 2018 study, Kem Muhibah participants took the same questionnaire thrice - before the camp, immediately after the camp and one month after the camp.

The findings are still being analysed, but the preliminary findings are encouraging, researchers said. The findings do not represent the nation, and it is not intended to be. The aim is to see if the intervention worked and how they can be improved.

In the preliminary analysis, the researchers found both Chinese and Malay participants to have reported better attitudes towards other ethnicities immediately after the camp.

Among others, they reported a higher willingness to engage with other ethnicities, and to a greater degree, saw other ethnicities as part of their own group.

However, after a month, this improvement only sustained among the Malays. The effects did not endure among Chinese participants.

“This may be due to some elements in their immediate or wider environment that undermined the effects of the camp and/or emphasised their minority status,” the researchers found.

Even so, they noted, the Chinese participants started off with already better attitudes towards Malays and Indians.

This means, even though the effects of the camp did not endure after a month for Chinese participants, their views of other races were “still markedly positive” compared to Malay participants.

The findings for Indian participants could not be analysed because the numbers were too small, which made statistical comparison unreliable, they said.

However, at face value, it appeared that the twelve Indian students had positive views of other races and were willing to connect.

Speaking to the Indian students, it appeared that although they now live and go to school in a monoethnic environment, many had attended either national school or national type Chinese schools at primary level, or national secondary school (SMK) for a few years before transferring.

In other words, this was not their first exposure to peers from different races - even though their previous interactions were not always positive.

N Karthikreyan, 16, enrolled in MySkills Foundation’s vocational residential school after dropping out of SMK. These days he is happier training to be a chargeman.

Having attended Tamil vernacular primary school, he made his first non-Indian friend at the age of 13 - a Chinese boy called Tan Chee Swan.

He could also name his first Malay friend - Azrul - whom he became friends with when they joined a study group together. Social media helps them remain friends, he said.

“In my previous school, SMK, there were fights. Indian school gangs would fight with Malay gangs, or fight with Chinese gangs. But I had friends from all races.

“My parents said we can be friends with the Chinese and the Malays. But we shouldn’t do wrong things like getting into fights,” he said.

Fresh friendships

Abim secondary school principal Rogayah Sebli was among the champions of Kem Muhibah.

“I felt sorry that my students were not experiencing what I did growing up in a national school in Kuching. I knew it would be difficult for them to adjust when they graduate, go to university and join the workforce later,” she said.

“I didn’t want them to be syok sendiri, that they think this world or this country is only made up of Malays,” she said.

She doesn’t believe one camp could change their entire mindsets but a recent incident has made her hopeful.

Recently, she said, Abim secondary school students were invited to attend a Chinese New Year celebration at a Chinese independent school in Klang. The first to sign up were Kem Muhibah participants.

“I wasn’t sure about opening it up to them because they had exams coming up.

“But they came to me and said: ‘Teacher, we really want to go.’ Because they wanted to visit the friends they made during Kem Muhibah,” she said.

Lee Soo Wei, a Kuala Lumpur Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall (KLSCAH) youth wing member who volunteered as a facilitator, said she hopes these fledgling friendships would sustain the test of time.

She believes the skills the participants learned confronting their differences will help them sustain their friendships in the face of heated debates along with race and religious lines in the wider society.

“The older they get, the more they will absorb (what is happening out there) and I hope they can interact with their friends on these issues; be open about it and speak about these matters more comfortably.

“They are young, but at least they now have the basic concepts (on how to navigate our differences); they no longer harbour stereotypes (which fester) when people avoid talking about the sensitive issues.”

In this social experiment, all eyes were trained on the subjects. Like lab mice, the children were fed stimulus and their reactions were meticulously measured.

But on the sidelines, something else was also happening.

Mohamad Khairuddin Zahari, leads Persatuan Pelajar Islam Selangor (Pepias), whose members volunteered as facilitators and contributed to formulating the camp modules.

After months of working together, Khairuddin said he now counts KLSCAH youth volunteers as among his good friends.

“In fact, we just played badminton together the other day,” he said.

“We started off wanting to help these participants get to know each other, but it turns out, the committee members are becoming friends, too,” Khairuddin said.

It is a happy accident they didn’t account for - something the researchers hope they can measure in the future.

They may have a chance to soon. The next instalment of Kem Muhibah is already in the works, this time in Negeri Sembilan.

Six decades after Merdeka, the process of learning to live together continues - one camp at a time.

Do you like this report?

Reports like this consume a lot of our resources to produce. Please consider giving a small donation as a token of appreciation so that we can continue to create more projects like this.