At 14 and 16, Afghan brothers Ayan and Farhan were ordinary teenagers living in Quetta, Pakistan. Going to school, playing football, running errands for their mother.

One day, their mother sent them to a neighbouring town to buy some medicine which was not available where they live. It was a journey they had done many times before.

It was a journey that would change their lives.

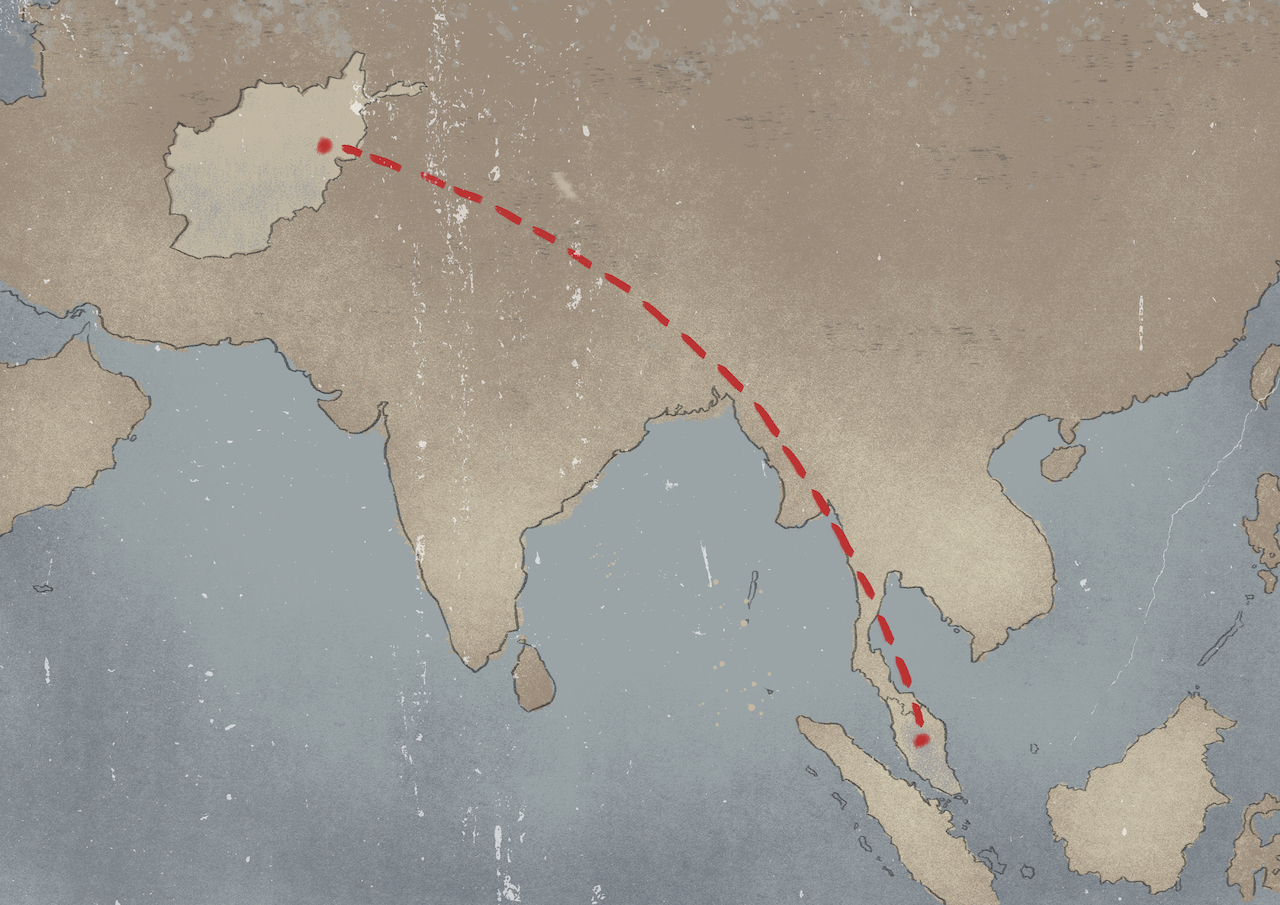

Little did the brothers know that this would be the last time they would see their mother and the place they grew up in - or that it would be the start of their long path to Malaysia, on their own.

This is their story as told to Aidila Razak.

Before we were born, there was a civil war in Afghanistan, where we are from. My father was a farmer, and at the time my two eldest siblings had been born.

My father and uncle were landowners. Before the civil war there were land disputes where some of the land was seized by force. My father and uncle stood up against this. This made them influential in the area.

He gained more and more influence and when the civil war happened, he became targeted and so my family - my parents and two eldest siblings - fled to a place called Hazara town in Quetta, Pakistan.

In Hazara town, my parents had four more children. We (Farhan and Ayan) are middle children, number four and five. We never had documents.

Quetta is a very big city, but we mostly stayed within Hazara Town. It was a small part of Quetta. We rarely went out of the town.

The streets of Hazara are small, there are not many vehicles and kids would play in the streets, with kites and marbles. Before our father died, we would sometimes help him at his clothing store. On most days, we would go to school and spend time hanging out with friends in the streets, playing football.

That day, our mother sent us to a nearby town to buy some medicines. We had done so many times before. But this time, there was a road block.

They took our phone away and took us to the police station and kept us there for two days. We were not allowed to contact our family.

On the second day, they put us onto a truck. It was night time. They didn’t tell us anything. There were many others in the truck. Finally, we realised, we were moving towards to Afghan border.

On the way to the border we were thinking of our family, our mother. We were worried for her - what she might be thinking that these two boys had gone off and not returned.

The truck just left us on the Afghan side of the border. This was the first time we were on Afghan soil. There were others who were deported at the same time, but they didn’t bother about us. We didn’t know what to do, we were scared.

There were shops at the border, and we had some money which our mother gave us for the medicine. So the first thing we did was buy a phone and a sim card to call home.

In that phone call, the one thing we remember our mother saying was: “Do whatever you can, just come back home.”

She said that there are people who can help you, who can just send you back to Pakistan if you pay them.

At the border, there was a hotel. Our mother told us to go there and ask for someone who can take us across the border. We didn’t know who we could trust, but we had no choice.

We tried to cross the border three times in the three days that we were at the border town.

The first time we tried to cross the border, it was a normal crossing. The agent was supposed to speak to the border guards and we were supposed to cross. But it didn’t work. The borders were quite strict. The same thing happened the second time.

It was at night, very dark when we set off. We could only go by moonlight. We followed a man who led us into a forest, through the mountains. We didn’t know where we were going so we just followed. We continued like that for several hours.

But still, we couldn’t cross. The borders were strict. We couldn’t reach the other side safely. So we turned back.

Our mother told us it is dangerous to stay in Afghanistan and that people who was against our father would look for us if they knew we were in the country. She said: “Find a way to get out of Afghanistan”.

My eldest brother, who had migrated to Australia, had this idea that if we couldn’t cross by land, we can try crossing by air. To do this, we needed to head to Kabul and apply for passports. With the passports, we thought, we could get visas and board a flight to Pakistan.

Kabul was more than 500km away from the border, and knowing what our mother told us about the dangers meant the journey was very frightening. But we had no choice.

Getting the passport was straightforward enough, it took us a week and in that time, our brother had managed to wire us some money to survive. After more than a week of uncertainties, things were looking optimistic. But what we didn’t know was getting a visa and a flight to Pakistan was impossible.

Relations between Afghanistan and Pakistan were strained at that time, and there were no flights between the countries. That’s when we decided we would travel to any other country - whatever to get out.

We visited a travel agent, and that agent told us with our Aghan passport, the only place we can get a visa to at the time is Malaysia. We knew nothing about Malaysia. But our brother said, ‘Okay, from Malaysia you can go somewhere else.’ So we agreed.

We didn’t bring anything with us. We had a few pieces of clothing we bought from Kabul and some money my brother had sent to us. That was all.

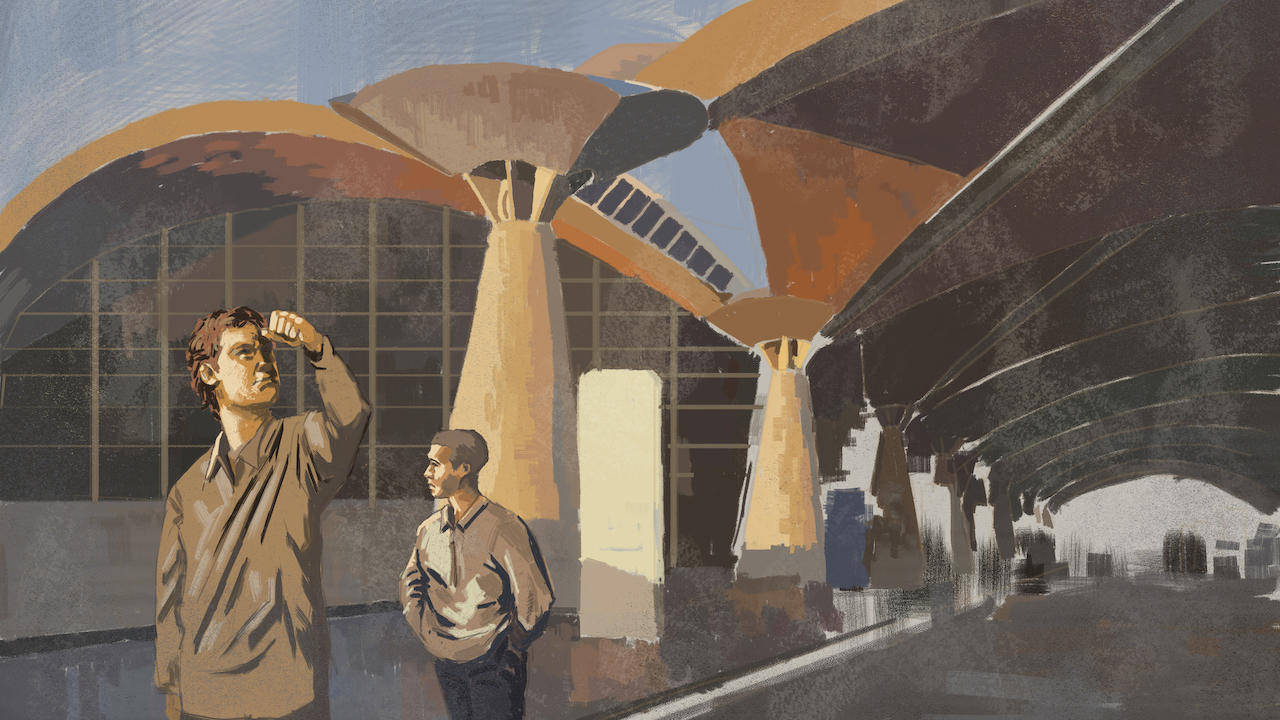

We were totally confused throughout the plane ride to Malaysia. We worried about what would happen when we land? Who would help us? How could we communicate?

Things went smoothly at the Kuala Lumpur International Airport. We had visas so there were no issues at immigration. But when the doors opened at the airport, we were shocked. When we left Afghanistan, it was cold. Here, it felt like someone was throwing flames at us.

We had no idea where to go so we called the travel agent, who booked our flights for us. He told us how to get a taxi and then to tell the taxi driver to take us to Ampang.

“Ampang is where your people are,” the travel agent said. But we didn’t know anyone there. So our plan was to head there and listen out for people speaking our language.

We reached Ampang in the afternoon - maybe about 3 in the afternoon. The taxi driver stopped us near Ampang Point. There were not many people on the streets at the time, and no one who spoke our language that we could hear. So we decided to just sit by the side of the street to wait.

Then amazingly, not long after, a group of men passed by and we heard them speaking Persian. They too, stopped when they saw us.

“Are you new here in Malaysia?” they asked. “Do you have a place to live?” We told them we had no one. They took us to their small apartment nearby and told us they would help us.

It was through them that we realised our plan to head to Australia to reunite with our brother would not be so easy. From them, too, we learnt we are now refugees.

They told us the best thing to do was to register with (UN agency for refugees) UNHCR, and maybe UNHCR can help us.

We stayed at that apartment for two months, and all the time, the others in there helped us. We had never cooked before, so initially we survived on Maggi instant noodles until the young men in the apartment taught us how to cook simple meals.

UNHCR was very helpful. We were issued a card - something we never had before in Pakistan. Before we had the card, we were worried because we only had the visa document, and that was expiring.

We moved out of the apartment in Ampang when we were connected with Suka Society, who help minor refugees who are separated from their families. Suka helped us find shelter with a foster family and find a school.

It has been two years since we landed in Malaysia. When I tell people our story I tell them what we went through feels like when you’re in water, and the waves just take you to wherever it takes you. Mostly you don’t have control but you have to keep going, keep being strong, continue wherever it takes us.

Be patient and be strong. If it takes you to an island, live on the island. If it takes you to another country, just live in that country. Get used to that country. Live.

Actually, we are lucky. We had our brother to guide us at first, and then they guys we met in Ampang and other refugees who helped us understand the process, and then Suka.

There are others who came to Malaysia and had to spend the nights in parks because there was no place for them. After that they have to start working to support themselves, even those that age.

When we turn 18, Suka would not be able to help us anymore. It may be a frightening prospect but we don’t think it is not so scary. Everything has a time, and that would be the time to move on. We will have to find a way to continue.

In an ideal situation, we would like to go to Australia and be with our brother but it is not up to us. It is up to UNHCR and up to the Australian government, so all we can do is stay here, study, wait.

The school we attend now is a school for refugees. There are four teachers who teach science, math and social studies. It’s not really what we hope for, but during this hard time, it is what we can get.

For the future, we hope for something bright. Be it in sports or in our studies, we want a successful life. But we also don’t know any refugee who has gone to university. Maybe the International General Certificate of Secondary Education (IGCSE) is the limit for us, refugees.

Since I have been here, I learnt that some Malaysians may view refugees as a different type of people. Maybe some refugees think that about Malaysians,too. But they’re totally wrong.

No one is different from one another. We are actually the same. The only difference is some documents.