When Zarif* told her about a young, suicidal refugee with nowhere to live, something moved inside Zurina*. A mother of a teenage boy herself, she couldn’t imagine her son stranded in a strange country, sleeping in a park, with no one.

“I told Zarif, ‘Go get him’,” she said.

It was quite late at night when Zarif got the call about the teenager - Ali* - who fled Afghanistan on his own a few months before. Having found temporary shelter, he was on the brink of living on the streets.

Unable to cope any longer, he was about to end his life. Zurina could not bear the thought of it.

At 19, Ali was only a couple of years older than Zurina and Zarif’s son, but the boy who turned came through their front door that night was half their son’s size.

“He looked like a 14-year-old boy. And he had this smile. My heart instantly opened,” Zurina said.

“I told him, ‘You can call me Mama.” She decided he would be her son.

Ali is among many young refugees who make perilous journeys to the unknown to flee dangers at home. Many end up in Malaysia.

According to the UNHCR, there are about 800 refugees aged under 18, and are in Malaysia without their guardians. Some are completely alone, others have family waiting, while others were separated from their parents en route.

It is a tiny fraction of the 177,920 refugees registered with UNHCR in KL in July, but in when it comes to unaccompanied minor refugees, “even one child is too many”, Michelle Fong, the agency’s Child Protection and Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Unit told Malaysiakini.

But this does not include many who are not registered with UNHCR, or other young refugees like Ali, who at 19 is no longer a minor, but would need the same support as a child of 17.

Some young refugees were bundled off by parents who hoped that distant relatives or neighbours abroad might help shelter their children and keep them safe. Others, like Ali, found their way to Malaysia because it is among the few countries which issues visas for people of their nationality.

For many, Malaysia was a place they had never even heard before.

A plot for an honour killing

Ali’s story begins in a village in Afghanistan. As a young boy, he was carefree and rambunctious. His stories of his childhood were of tree climbing and wrestling with goats. It was a happy childhood.

Part of a large tribal family, Ali’s life was comfortable. Occasionally, he told Zurina and Zarif, there were bombs “but not so often now, maybe just once a week”. Someday, he said, Zurina and Zarif should visit his village.

But he cannot return.

As Ali became older, there was something about him which his family could not accept - something so sensitive that it would later mean even the Afghan refugee community in Malaysia would reject him, leaving him without no one that night Zarif brought him home.

It was something his foster parents wouldn’t allow Malaysiakini to publish - and something which could get him killed.

One day, when he was supposed to be asleep, he heard his uncle tell his wife that they should poison his food, bit by bit, so slowly he would die. He told his mother. She decided to get him out.

It took three lies - they always said they were off to the mosque to pray away Ali's "affliction", the thing their family felt was an abomination. But in fact, the first time, they went to the pawn store to pawn his mother’s jewellery, the second time, to get a passport, visa and flight tickets, and the third time, to the airport, where he would see his mother last.

Recounting the start of his journey to his foster parents, Ali said he would watch Youtube videos to know what to do before he went to the airport. How to check in for a flight, board a plane, where to go in transit - he transited in India - and where to collect his luggage once he landed.

In Kuala Lumpur, where he was waved in by immigration unceremoniously thanks to the student visa his mother acquired at the cost of RM12,000, and collected by an agent at the gates.

“The agent took him to a park somewhere in Shah Alam, and left him there. He told us he arrived about 6 am, and he just sat there, not knowing what to do,” Zarif said.

“He just sat there waiting for someone.”

The sun set. Maghrib call to prayers filled the air. Darkness descended on the park. Afraid to do anything, he waited.

At 8pm, someone came.

The agent - who at the park told Ali he was only paid to collect him from the airport and nothing else - had somehow told friends about what had happened. One of the agents’ friends came to look for Ali.

It was this friend - an Afghan postgraduate student - who sheltered Ali. They became close friends, room mates, sharing a studio apartment. Ali soon enough found work as a kitchen hand and was contributing to the household expenses. The friend took Ali to UNHCR, helped him arrange for an interview so he could be registered as a refugee, showed him the ropes.

But around the time the pandemic hit, the friend would graduate from his postgraduate course, and would need to return to Afghanistan. Ali would lose his job at the restaurant. He would be left alone - desperate, suicidal, and then finding his way to Zarif and Zurina’s living room.

The climate of fear

Today, just a few months after that night, it feels unthinkable to not have Ali in their lives.

“He really opens your heart,” Zarif said. “The way he sees things - he tells me that Malaysia is so green and beautiful that he wants to hug Malaysia - it gives us a different perspective.”

Although Zurina and Zarif consider Ali their adopted son, they know this is not legally-binding. There is no legal way to adopt Ali because he is no longer a minor.

Despite allowing UNHCR to operate in the country, Malaysia is not party to the 1951 Refugee Convention and does not have an asylum system regulating the status and rights of refugees. Under the Malaysian sun, Ali is an undocumented migrant.

This means he could be arrested by immigration at any time and deported home to an uncertain fate. It also means Zurina and Zarif, too, could be found guilty of harbouring an “illegal immigrant”. This is why they chose to speak to Malaysiakini under pseudonyms. Ali, too, is not his real name.

The couple says the fear of arrest is greater these days with xenophobia reaching fever pitch and the government taking a harder stance against undocumented migrants amid the pandemic.

“In this climate, it’s not safe to be out there,” Zarif said.

This meant they have barred Ali from wandering out on his own, even to find work to contribute to the household expenses.

One day, stuck at home, Ali decided to cook an Afghan dish, with instructions from his sister. It was the first time he had made mantu, a type of beef dumpling. It was the best dumplings his foster parents ever had.

He cooked more and more dishes from home, astounding Zurina and Zarif every time. This sparked the idea of starting a home-based catering business for Ali, something for him to earn some pocket money.

Their customers were mostly Zurina and Zarif’s friends and family. Ali would cook in their kitchen and Zarif would become the delivery boy. Soon, it was too much to handle.

“Ali would say he wished his sister was with him to help him, because at home, he didn’t have to do any of the cooking or cleaning,” Zurina recalls.

And then, his wishes came true.

After the state borders reopened, the family traveled to Zarif’s hometown in Penang to introduce his new son to his mother.

On the way home, Zarif’s phone rang. It was Aliza Haryati Khalid, a friend, who then headed MSRI, an organisation which provides services to refugees in Kuala Lumpur.

“She said, ‘I’m sorry, I have to ask you because I am at my wit’s end. Could I put her in your house?”

Like before, the couple said yes.

When they arrived from Penang, Aliza and Alia* were already waiting for them at their apartment building. As they sat in the living room, Alia, an Afghan girl of 16 with long hair and full cheeks, was crouched in a corner, unable to look at anyone.

“She was so small and so scared,” Zurina said. “You wondered what had happened to this girl.”

By the time Alia found her way to Zurina and Zarif’s home she would have been shuttled through three countries and bounced from shelter to homes.

In her hometown one morning at about 4 am, her mother woke her and told her to be quiet and pack her bags with some clothes. Without explanation, Alia’s mother gave her some juice, biscuits, a bit of cash and her own mobile phone.

They would sneak out of the house, and they would meet an agent before day break.

“You will follow this agent, and keep this phone as evidence,” her mother would tell her. This was the last time she spoke to her mother.

In the phone’s photo gallery were pictures of Alia bruised and battered at the hands of her abusive father. Her mother felt there was no other choice but to send Alia away as far as she could. With her mother’s phone with her, there was no way to stay in touch. She doesn’t know if her mother is alive.

In Kuala Lumpur, the agent sent her to an area where Aghan refugees are known to be, and a community leader took her to MSRI. The NGO helped raise funds to aid the community shelter her but soon the money ran out, the pandemic hit, and it was no longer feasible for the family that sheltered her to feed another mouth.

Desperate to find a place for this girl, Aliza called her old friend Zarif.

“I told her I couldn’t because we already have Ali and our house is so small, but she said just for one week, so we said ok.”

A month passed, then two, now three, and Zarif and Zurina have not made that phone call to their friend Aliza to ask how long Alia would stay. She is now their daughter, their sons’ sister. It would feel unbearable to say goodbye.

A pain without words to describe

In many ways, Zarif said, it felt predestined.

Ali had longed for his sister, and through their door came this girl, who spoke his language, and even his dialect.

In each other they found a place to confide in, someone to share how they feel when it is too difficult to express in English or Bahasa Malaysia - languages they are picking up at tremendous speed.

Sometimes, at night or in the morning after dawn prayer with Zurina, Alia would weep wordlessly, unable to find the words to express how she feels. She would point to her chest and say, “Pain”.

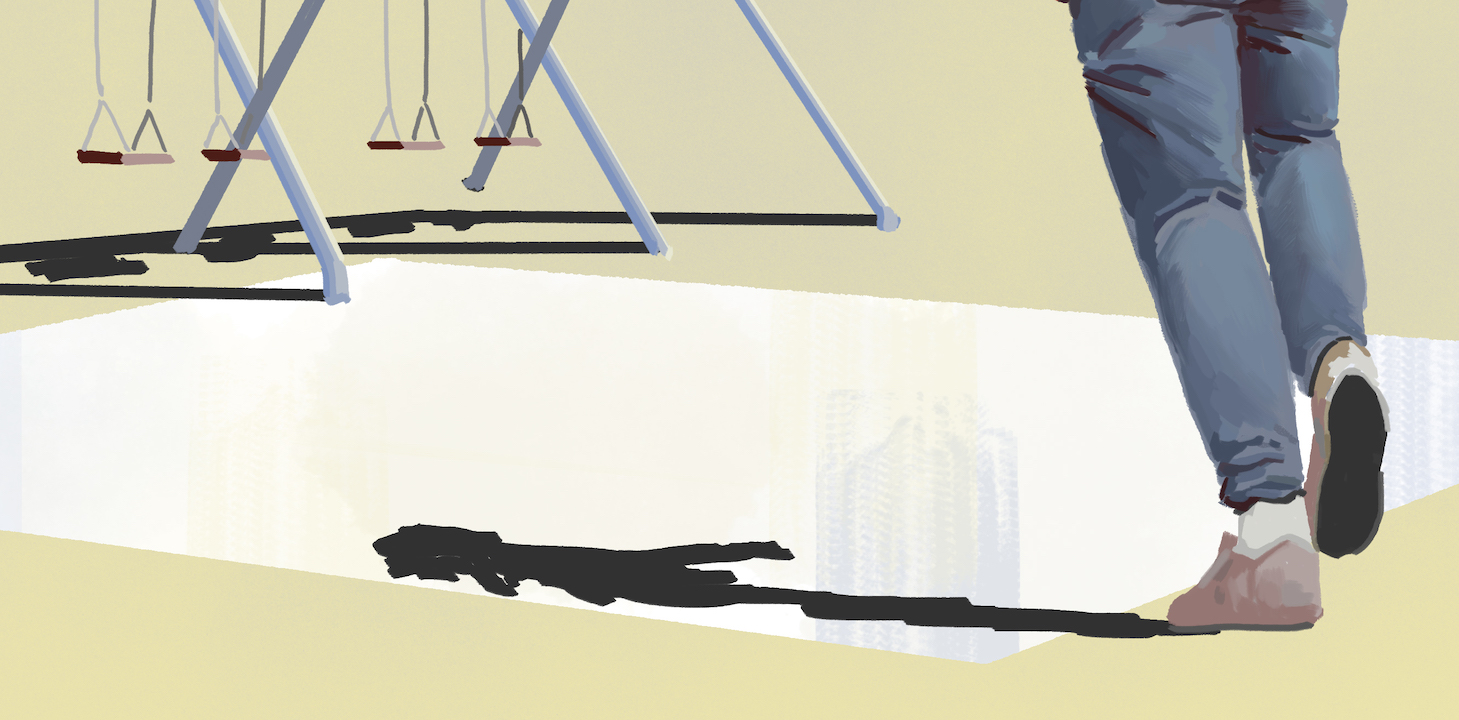

Other times, she is a giggly teenager on a girl’s day out with her foster mother at Sephora or running towards the swings at a public park, her long hair fluttering behind her.

At home, amid the moments of unspeakable torment, there are pillow fights and laughter as she and Ali quarrel in the kitchen - Alia, now, an integral part of the catering business.

Her child-like demeanor make her foster parents believe she is 16 as she insists, and not 21 as her passport states. It could be that the agents had made her older for easier travel, her foster parents posit.

They don’t argue about it - it sends Alia into a torrent of emotions, being disbelieved over something so fundamental.

Soon her UNHCR assessment interview will take place, and this age factor may change many things about her journey.

If she is 16 - a minor - she would be deemed more vulnerable than an adult, and may be afforded other services.

She could be placed under programmes where unaccompanied minor refugees are placed in foster homes, sent to school and have their welfare taken care of.

As a minor unaccompanied girl, she would be deemed more vulnerable, and this may raise her chances of being resettled in a third country.

But Zurina and Zarif hope the story she tells UNHCR’s interviewers will be consistent with her passport. They worry the inconsistency might jeopardise her application for asylum and chances for resettlement.

Ultimately, Malaysia is only a temporary stay.

For as long as Ali and Alia are with them, Zarif and Zurina’s hope they can support their dreams.

In the best scenario, they would be resettled in a third country, where they would have rights and can put down roots and pursue their ambitions.

“They have high ambitions. They want to go to school, start a business, be a big boss. They’re not just thinking of survival, they also have dreams,” Zurina says.

With Alia on board, their little catering business is thriving and the teeagers work hard to keep up with orders and the food continues to gain rave reviews.

The orders are piling in at such a rate that Zarif is no longer able to be their delivery boy, and they have had to resort to runner services.

“They work very hard and they’re thriving,” Zurina says, but they also share how they wish they never had to leave their country, their mothers, their sisters.

Together, the family travels to Afghanistan via Youtube, the teenagers narrating videos about places where they grew up. One day, they hope their new family could meet their mothers.

“This journey with them has been humbling for us. We are not rich people, we also have to make ends meet. But we are still able to give them something they need - a safe place,” Zurina says.

“In fact, we are not giving them much, only a little bit of our hearts, a little space in our homes, a little love. That’s all."

* Names have been changed so their identities would remain confidential.