When Sharifah Shakirah was only five years old, she was stuffed in a boat with strangers.

Separated from her father, who fled violence, and her mother, who was arrested when she tried to join Sharifah’s father, she was sent to find a way to her father, on her own.

Handed over to human traffickers by relatives, she would travel by sea and by land, traversing jungles by foot and then by car to reach her father in Malaysia - a father she had no memory of.

This is her story as told to Aidila Razak.

I have very little memories of Myanmar. When I was two, my father left us. On the day he left us, he had witnessed members of the Burmese Army commit violence against civilians. Fearing for his life, he fled. He never even said goodbye.

We are Rohingya Muslim and we lived in the Arakan state. For the Rohingya community, men are the breadwinners. So when my father disappeared, my mother was left to care for us - two daughters aged two and one - without the means to. Unbeknownst to her, she was also pregnant with my brother.

There are very little that Rohingya women can do to earn a living at the time. My mother started working in other people’s houses. Soon, she heard from our father, he was in Malaysia.

The village that we lived in was surrounded by Buddhist villages hostile to us. The situation was getting more and more violent by the day. It escalated when some Buddhist monks started instigating followers to burn down Rohingya houses and shops.

My mother felt it was no longer safe to stay - we could be killed at any time - so she decided to also flee and take us to our father.

As Rohingya, we couldn’t just leave if we wanted to. We didn’t have any passports. We couldn’t just take a plane out of the country. It was illegal to leave Arakan state without permission. Our movements were heavily restricted, it was like living in a big prison.

So my mother arranged for us to escape by boat - from Arakan (Rakhine state) to Rangoon (Yangon), and from there go on another boat to Thailand, and then Malaysia.

It was around subuh (before dawn) when we boarded the fishing boat in Arakan. I was already three by then, my sister was two and my brother aged one, still breastfeeding.

When we arrived in Rangoon, we were placed in a building, like a shop with the shutters brought down. We were the only children in that place. There, the traffickers demanded payment.

My mother had planned for my father to send through the money by the time we got to Rangoon, but it didn’t arrive in time. So my mother negotiated a deal - release us children to relatives, and she would stay until the money came through.

But I would not see her for another two years. Somehow after we left, the authorities raided the place and everyone was arrested. My mother went to prison for two years for traveling without proper documents.

The relatives who collected us separated us between them - I stayed with a family in Mandalay, my siblings in Rangoon. I had never met these relatives before. I stayed with them for two years.

They were a happy family with their own children, but they abused me. They hit me until my teeth broke. I get emotional just thinking of those days and I am still coping with the trauma today, but thank God that it was not sexual abuse like so many refugee girls I have met since then. In fact, the family dressed me up as a boy, and shaved my head to look the part. I still don’t quite know why.

Sometimes, when at their place, there would be people coming to look for me - police or someone like this. They would say they know my mother had three children and they were looking for the children. I would have to hide inside the house.

Those were really the hardest moments of my life. I didn’t understand what was happening. I remember thinking of my mum and crying every night. I cried for her hugs, for her love, for her company. Later she told me she survived prison by thinking of us every night.

When we were separated, I was told I just needed to wait until she was released and then we could be reunited and resume our journey to meet my father. This didn’t happen in the end. Instead of releasing her in Rangoon, she was deported back to Arakan. It was then that my father decided to arrange for us to travel on our own.

My brother, who was 3, went first, and then my four-year-old sister and finally it was my turn. My relatives took me to a house and left me there without goodbyes. They told me I was going to meet my father. I had no memory of him so I thought of a photo I saw of him once. I thought I would see my siblings, so I brought with me a little yellow toy mouse for my brother.

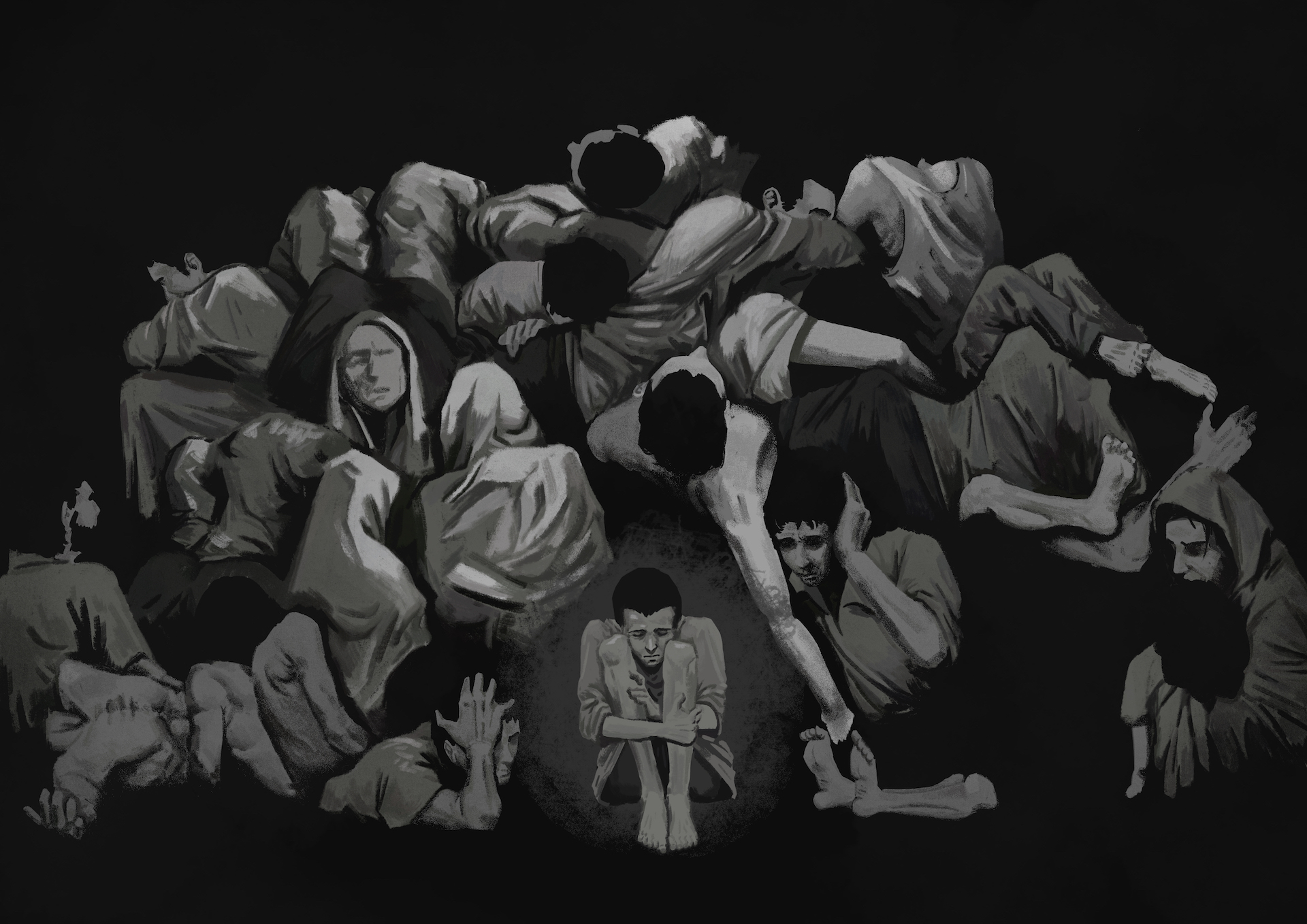

I was really scared, handed over to a stranger, again. The trafficker, a Burmese woman, came on board with me. We were not allowed to bring anything with us, so my bag and the toy mouse was thrown overboard. We crouched in a covered area of the boat, with so many others, heads, bodies, piled up on top of each other. And people got sea sick, vomiting onto each other.

It was the start of a two-week journey. The journey was from Myanmar to Thailand and Thailand to Malaysia. It is hard to remember details - like what we ate - but I remember the feeling of being terrified. When we walked in the jungle at night and stayed in shack in the middle of the forest, the trafficker would say, “Don’t walk there, or you’ll get killed.” It seemed everything would get me killed.

The journey was dangerous - one could be exploited, detained, tortured or arrested - and I had no one to look out for me. Except maybe an angel who was guiding us. That is the only explanation I can think of how I survived the journey as a young child, when other adults were dying around me.

We crossed into Malaysia by bus. I was told the colours of uniforms worn by the Malaysian police, and to act normal and don’t be scared if encountered. And then the next thing I know, they told me “This is Malaysia, you’ve arrived.”

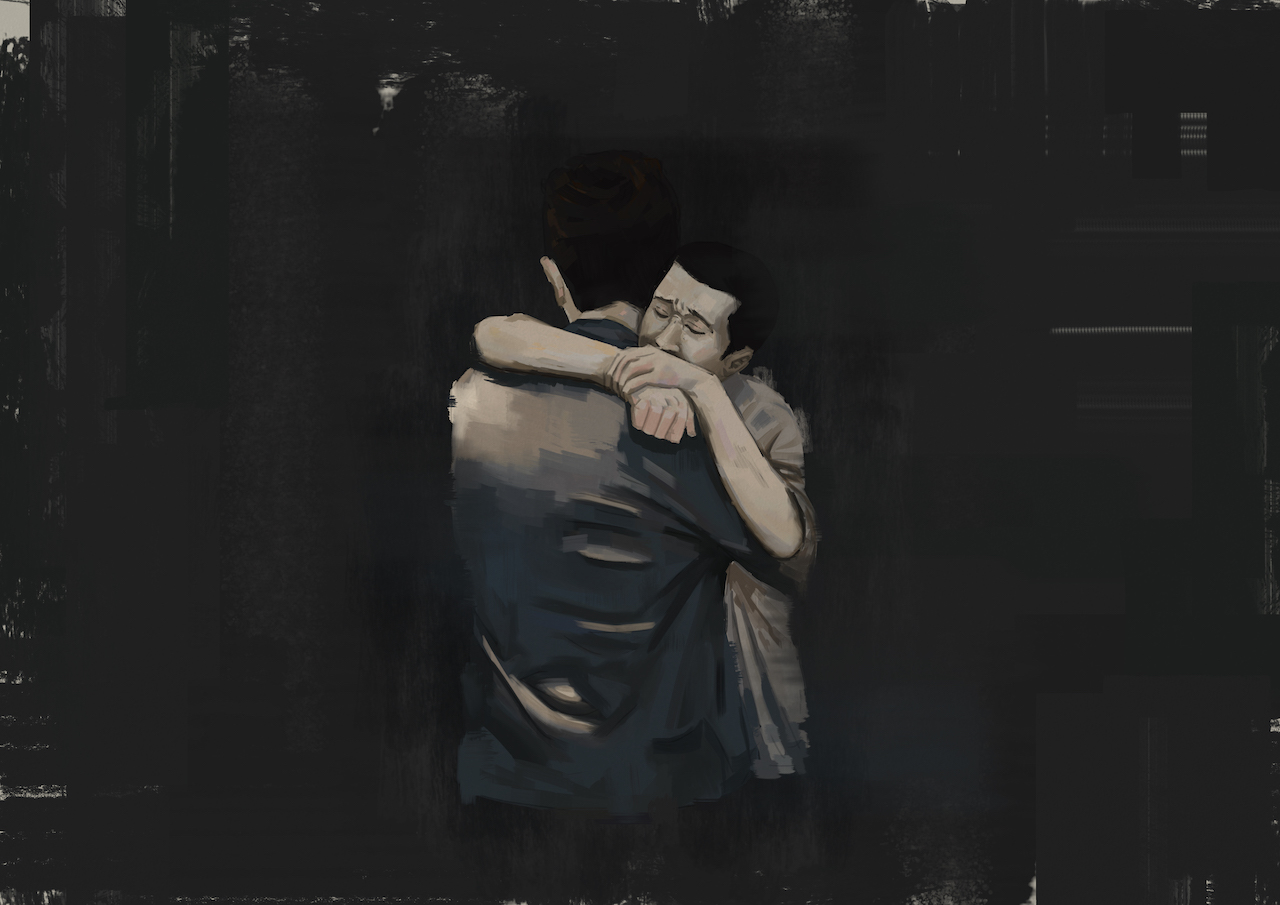

My father was waiting across the street when I got off the bus. Of course, I didn’t recognise him, but a man told me “That is your father.” I remember feeling completely overjoyed that I ran and hugged him. He was shocked. He expected a daughter, but a boy in shorts and a shaved head was hugging him.

My mother arrived two months later, and finally our family was reunited. I don’t remember it now but my mother said we had forgotten about her and didn’t know who she was. I think maybe it was just that we couldn’t really process how to feel.

This inability to process my feelings - it happened to me again when I got resettled in the United States three year ago, and was reunited with my parents who were resettled there before me.

They came to pick me up at the airport and I was very happy, but at the same time I couldn’t really articulate how I felt. I was quiet for at least two days, and then even after that I would cry in intervals for no reason. I just didn’t understand what was happening to me.

It is hard for me to revisit all that had happened but I also think the difficulties have helped me become who I am. When things are hard, I think of that journey and that time and tell myself, “You have survived more difficult things before.”

It is also why I founded my organisation, the Rohingya Women Development Network. I believe also that Allah had made me go through all the troubles and challenges because He wants me to tell the people. He made me strong so I could help people, this is my purpose in life. I was created to help my people. It is an immense responsibility but I am doing my best to rebuild my community.

Because I was only resettled last year at the age of 24, I spent most of my life in Malaysia and so Malaysia is also sort of home. I have siblings born in Malaysia, and we all speak to each other in Malay. My younger brother can hardly speak Rohingya, and prefers to speak Malay.

It doesn’t mean everything was smooth sailing in Malaysia. Realising the importance of education, my father worked hard so he could send me to a private Islamic primary school. There, I was bullied, coming home sometimes completely drenched because the other students would throw water on me just for fun.

Sometimes, when things get really bad I would tell my mother I wanted to go back to Myanmar, and she would look at me with this look like she was just completely at a loss.

Many of the Rohingya refugees who were born in Malaysia or left at a young age integrate very easily into Malaysian society. We speak the language, dress like locals, we’re just like Malaysian kids.

But even though I dress and speak like a Malaysian, something inside of me always felt I didn’t belong, and that being in Malaysia is just temporary - even though I spend close to 20 years there.

Physically, I was in Malaysia, but mentally in Myanmar, and all the while trying my best to be the best version of myself so the locals would accept me. Because I had been rejected, and rejected, and rejected all my life and I didn’t want to be rejected again.

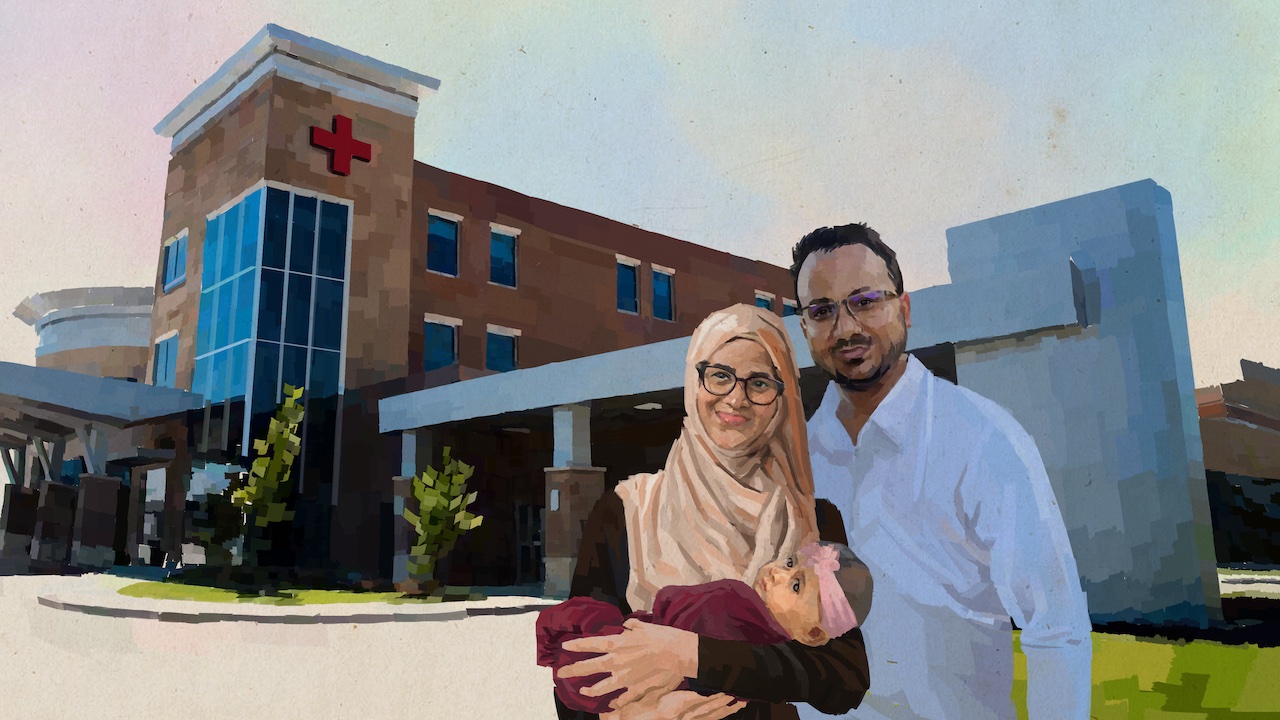

Here in the US, my siblings and I are in college or school. We have bank accounts. My husband has a drivers’ licence. My parents, who are now US citizens, own a house.

If you come visit the Rohingya community here, you’ll find them speaking Malay to each other, cooking nasi lemak or laksa - it is our way of showing gratitude to Malaysia, the people, the language and the culture.

We are living examples that the Rohingya refugees are only seeking temporary shelter in Malaysia. While we are there, let us study, let us work, let us contribute.

One day I hope to return to Malaysia and show my children where we grew up. But this time we will enter legally with legal status.

My eldest child was born this year. I waited until I was resettled to start my own family because I didn’t want my child to be a refugee, to go through what I did.

She is the first person in my family to be born a citizen. She belongs to a country and she has human rights. She is protected by the law. She is free to choose what she wants. That is the best thing I could give to my child.

Now 25, Sharifah resides in Texas, United States with her parents, siblings, husband and daughter Amira. She is currently studying for the General Educational Development test so she can attend college. She is the founder of the Rohingya Women’s Development Network. Last year she was nominated for the US Department of State's International Women of Courage award.