Jan 16, 2025

On-demand connectivity to rail stations may be a game changer for KL public transport.

As commuter rail networks expand, more and more Klang Valley residents have access to fast rail transportation.

The Rapid KL lines have grown tremendously since the first LRT line opened in 1996.

But still, only about 10 percent of its residents use the Rapid KL rail system - be it LRT, MRT, or Monorail, on a daily basis.

One major problem: first and last-mile connectivity. Many of the stations are not very accessible to commuters.

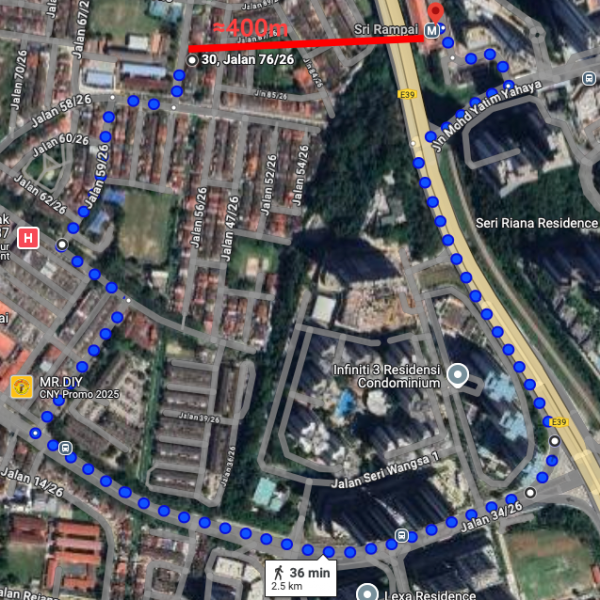

Take for example the Sri Rampai LRT station, located in a mixed land use area surrounded by shopping malls, residential areas, condominiums, and commercial buildings.

But to walk from the nearest residential area - Taman Sri Rampai - takes 30 minutes, or about 2.5km. This despite the direct distance being only about 400m, researchers from the University of Nottingham Malaysia and Universiti Malaya found in a paper published in 2020.

Looking at three stations - Sri Rampai, Asia Jaya, and Miharja - the researchers found walkability to the stations pale in comparison to other metropolitan areas like Singapore where the average walking distance to a rail station is 631m, or parts of South Korea where it is under 800m.

The same is found for stations on the newer MRT lines, like the Bandar Utama station, which is just 150m east of Jalan Burhanuddin Helmi 2 in the Taman Tun Dr Ismail residential area.

But a walk to the station will probably take more than half an hour, much longer than the 10-20-minute rule of thumb to measure walkability to mass transit stations, expert Muhammad Zulkarnain Hamzah said.

How to solve the connectivity issue?

In sprawling cities like KL, buses can be one solution to solve the connectivity gap left by rapid rail transit, said Zulkarnain, the co-founder of advocacy group Transit Malaysia.

But buses often get stuck in KL’s choking traffic jams, leading to unreliable service and longer waits for commuters. Relying on bus services means a short 5km commute could take up to an hour.

Enter Demand-Responsive Transport (DRT), a new urban transport experiment that could change this all.

This is how it works.

The DRT solves two issues - commuters don’t have to wait very long for one, and because it only travels within a small radius, passengers won’t get stuck in long traffic jams or need to go in large loops to travel a short distance.

The DRT service, now in a trial phase, covers much of Greater KL with three operators - Kummute, Trek Rides, and Mobi.

DRT service coverage areas

Zoom in to see the pickup/drop-off points.

What is the outcome so far?

Rapid Bus, the operator of Klang Valley buses, started its trial with 20 vans covering nine LRT stations. The response was so overwhelming that it has now ordered 300 more vans to add to the service.

With just 20 vans since May 2024, Rapid DRT moved 222,595 passengers in its first six months of operations, with most passengers waiting just nine minutes for a ride, and travelling an average of 11 minutes to their destination.

At the Alam Megah LRT station in Shah Alam, the Rapid feeder bus used to serve a paltry 40 passengers a day. But the DRT has tripled this figure.

When met, passengers said the DRT has helped them to better rely on public transport for their daily commute.

More importantly, the ability to book rides on-demand has also clawed back precious time that they used to spend rushing to the bus station only to wait for the next bus.

For busy urban dwellers, those extra minutes can mean additional time to rest or grab a quick breakfast - contributing to general well-being.

Not always perfect

But as with all new services, teething issues have emerged. The perennial traffic jam which has kept Klang Valley buses in standstills during peak hours can at times also affect the DRT, passengers say.

Also sometimes, the waiting time is not fixed, like you were already booked for a minute then the waiting time changed and you’re re-booked on to the next trip. But so far it has been helpful.”

But the service timing is sometimes off during peak hours, showing four minutes then suddenly changing to six minutes.”

A stop-gap measure?

Urbanist KL, a group pushing for better urban planning and mass transit, says the DRT has been a great addition to Kuala Lumpur.

However, it cautions that it should only be seen as a complementary service and not the end solution.

“While DRT has a role in the Greater KL mobility landscape, it should complement - rather than replace - more fundamental solutions like urban planning that is well connected to bus and rail transit, encourages walking and cycling, and a robust, frequent bus system.

“After all, DRT vans are still motor vehicles, which contribute to traffic congestion, pollution, and carbon emissions. It also operates within the framework of car-centric infrastructure, like wide roads and elevated highways, which is a major cause of the first and last-mile challenge.

“Addressing this issue at its root - by investing in better urban planning - would offer a more sustainable long-term solution than relying solely on a highly subsidised technology-based ‘quick fix’,” it said.

Transit Malaysia’s Zulkarnain agrees.

While the DRT can serve residential estates better than conventional buses, he says the real solution is proper urban planning.

This includes parking all urban transport assets under the financial supervision of the Finance Ministry and setting up a separate urban transport and planning authority.

This way, he said, RapidKL could better collaborate with a mix of stakeholders, including local councils, planning bodies, and the Works Ministry - and not just fall under the purview of the Transport Ministry.

“Singapore has the Land Transport Authority, London has the Transport for London, and Vancouver has Translink, so Greater KL needs to have its own regional transport authority in charge of all matters of transportation in a very urban area like Kuala Lumpur.”